Athena Review Vol. 5, no. 1

Records of Life: Fossils as Original Sources

37. Late Miocene Apes

Late Miocene Hominoidea in Europe

Dryopithecus

Dryopithecus

("oak tree ape") was discovered by Edouard Lartet (1856) at Saint-Gaudens, France in a context dated at about 11.5 mya. The type species was named Dryopithecus fontani. Since then, further fossils of Dryopithecus have been found in Spain, Hungary, and China, with two further species defined, D. widuensis, and D. brancoi.

("oak tree ape") was discovered by Edouard Lartet (1856) at Saint-Gaudens, France in a context dated at about 11.5 mya. The type species was named Dryopithecus fontani. Since then, further fossils of Dryopithecus have been found in Spain, Hungary, and China, with two further species defined, D. widuensis, and D. brancoi.Although classified as an ape (hominoid), Dryopithecus in its post-cranial anatomy in some ways more resembled an Old World monkey. Based on its wrist and arm structures, it walked on all fours using the flat of its hands, like a monkey, instead of the knuckle-walking used by modern apes. It probably lived in trees, using its arms to brachiate from limb to limb, as with modern orangutans and gibbons.

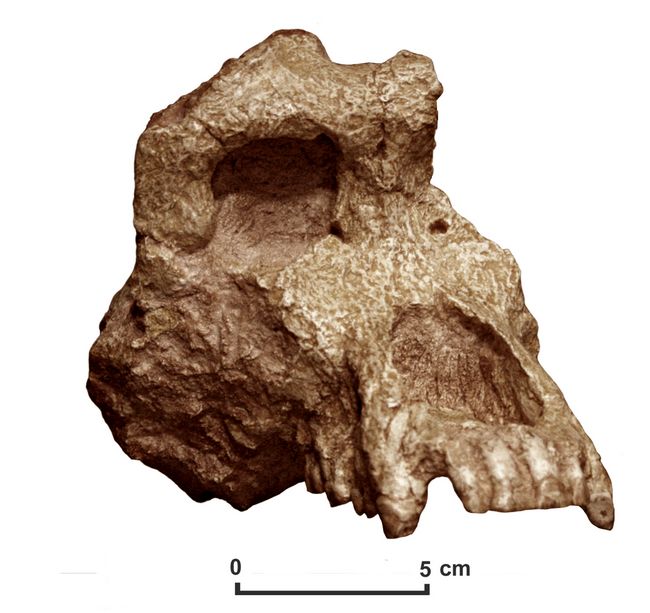

Fig.1: Skull of Dryopithecus fontani (Mus.Nat.Hist. Paris, cast).

The molar teeth of Dryopithecus showed a Y-5 pattern, with five cusps, typical of hominoids. The molars had thin enamel, suggesting that it ate soft leaves and fruit. Dryopithecus had a relatively large brain, and a gracile jaw that did not greatly protrude. In these respects it may be contrasted with the contemporary Sivapithecus from northern Pakistan (Begun 2004).

Several other European Miocene apes have been grouped by Begun (2010) in the tribe Dryopithecini, including Hispanopithecus, Rudapithecus, and Ouranopithecus.

Hispanopithecus

Hispanopithecus are Miocene apes first identified by J. F. Villalta and M. Crusafont (1944). The genus contains two species: H. laietanus and H. crusafonti. The fossils have been dated to between 11.1 - 9.5 mya. The body sizes of extant fossils provides strong evidence of sexual dimorphism. The males have been estimated to weigh about 40 kg and to possess prominent canine teeth, while females weight 22–25 kg and had smaller canine teeth. They had robust chest, arm, and hand bones and were probably adapted to tree climbing, with a diet of fruits.

The dental formula of Hispanopithecus, common to great apes, is 2:1:2:3 in both maxilla and mandibl3, with the Y5 occlusal surface present on the lower molars.

Anthropologists disagree as to whether Hispanopithecus belongs to the subfamily Ponginae (most closely related to modern orangutans) or Homininae (most closely related to gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans).

Pliopithecus

Pliopithecus was a Miocene ape found in Europe, It was discovered in France in 1837 by Édouard Lartet, with fossils later found in Switzerland, Slovakia and Spain. Six species have been identified.

In size it resembled a gibbon. with long limbs, hands, and feet, and may have been able to brachiate, swinging between trees using its arms. .

Fig.2: Skull of Pliopithecus

Ouranopithecus

Ouranopithecus was a Late Miocene hominoid represented by two species, O. macedoniensis (9.6–8.7 mya) from Greece and Bulgaria (de Bonis and Melentis 1977), and O. turkae (8.7–7.4 mya) from Turkey (Gulec et al 2007)

Ouranopithecus had thick molar enamel, and showed considerable sexual dimorphism, The most complete Ouranopithecus skull (fig.x) appears to be a male, but it has relatively small canines comparable to those of a female gorilla. Based on O. macedoniensis's dental and facial anatomy, it has been suggested that Ouranopitheines were dryopithecines. However, Ouranopithecines may be more closely related to the Ponginae subfamily of hominoids (including Sivapithecus, Lungfengpithecus, Khoratpithecus, and the modern orangutan, Pongo). O. macedoniensis shares derived features with some early hominins, such as the frontal sinus, a cavity in the forehead, but they were likely not closely related.

Fig.3: Skull of Ouranopithecus macedoniensis (Mus.Nat.Hist.Paris, cast).

Rudapithecus

10 mya

Rudapithecus, discovered by Miklos Kretzoi (1969) in Hungary

Late Miocene Hominoidea in Asia

Sivapithecus

Sivapithecus was a Miocene ape who lived in the Siwalik area of northern Pakistan, in the Potwar plateau region, between 12.5-7 mya. Originally discovered in the 19th century, it has been intrepreted as a fruit-eating quadrupedal

ape about 5 feet tall,

who probably spent most of the time in trees. There are three species.

including the the earliest, S. indicus; the largest, S. parvada; and S. sivalensis.

ape about 5 feet tall,

who probably spent most of the time in trees. There are three species.

including the the earliest, S. indicus; the largest, S. parvada; and S. sivalensis. Sivapithecus is considered to be the ancestor of the Southeast Asian ape Pongo pygmaeus, the orangutan, whose two varieties now live in Borneo and Sumatra. Sivapithecus and Pongo share several derived cranial features including a high degree of prognathism, oval orbits, a narrow nasal aperture, and broad zygomatic arches. In these features, and in their high, rounded braincase, the skulls of Orangutans differ from that of the African great apes (Fleagle 1999).

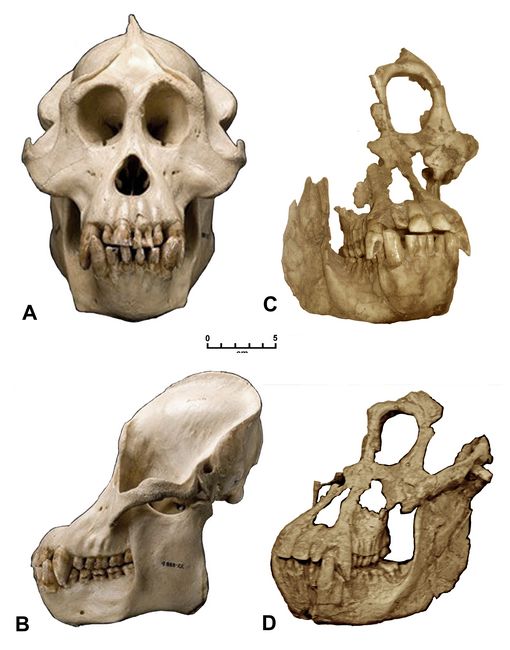

Fig.4: Orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) (A,B) and Sivapithecus (C,D) skulls in frontal and profile views.

The examples shown in fig.4, identified as male skulls, have prognathic or projecting faces with large canines and incisors. Like the orangutan, Sivapithecus showed considereble sexual dimorphism. The smaller, more gracile female skull of Sivapithecus was formerly thought to be a separate species called Ramapithecus, which from the 1930s through 70s was interpreted as a possible hominid ancestor, until conclusively identified in the early 1980s as a female variant of Sivapithecus (Pilbeam 1982).

Most authorities accept the hypothesis that Sivapithecines and other fossil apes from Asia are members of the lineage that includes the living orangutan, which is usually referred to as the subfamily Ponginae. Begun (2010) has grouped the Miocene taxa into two tribes, the Sivapithecines, containing Sivapithecus, Ankarapithecus, and Gigantopithecus, and the Lufengpithecines, including Lufengpithecus and Khoratapithecus.

Khoratapithecus

13.5–7 mya Khorat, Ba Sa Thailand.

Lufengpithecus

The Late Miocene Lufengpithecus from southern China is known mostly from hundreds of isolated teeth, principally from the sites of Shihuiba (Lufengpithecus lufengensis; ca. 6–7 mya) and several somewhat older sites in the Yuanmou Basin (Lufengpithecus hudienensis; ca. 7–8 mya) (Kelley and Gao 2012). The molar teeth are similar to those of the modern orangutan, There are also several badly crushed crania from Shihuiba (fig.5)

A significantly later juvenile cranium of L. lufengensis; was reported in 2013 at the site of Shuitangba in Yunnan Province, China, dating 6.1 mya (fig.6). This is only the second relatively complete skull of a young juvenile known from Miocene apes.The cranium of L. hudienensis from Yuanmou, YV0999, preserves nearly the entire facial skeleton, the palate with partial dentition, and most of the frontal bone. In contrast to the Shihuiba crania, it is remarkably well preserved and minimally distorted,

with the right side being almost completely free of distortion

Lufengpithecus has often been considered to be in the lineage of the extant orangutan Pongo, now confined to Southeast Asia but also known from the late Pleistocene of southern China. The new Lufengpithecus cranium (fig.6), however, shows little resemblance to those of living orangutans. It appears to represent instead a late surviving lineage of Eurasian apes, with some affinities to chimpanzees (Pan).

Southern China was less affected by climatic deterioration during the later Miocene that may have caused extinction of varous ape species in Eurasia.

Fig.5: Skull of Lufengpithecus lufengensis (Ji et al. 2013)

Gigantopithecus

Fossil evidence of the very large ape Gigantopithecus dates over the unusually wide period of 6.5 mya to about 300,000 BP, when it was apparently contemporary with Homo erectus. Most of the finds of Gigantopithecus are isolated teeth. Like Sivapithecus it has been found in the Potwar Plateau of India as well as in southeast Asia, where its fossil remains have been reported in detail by Ciochon (ref).

References:

Begun, D.R.. 2004. Sivapithecus is east and Dryopithecus is west, and never the twain shall meet. Anthropological Science. 113 (1): 53–64.:

Begun, D.R.. 2005. Relations among great apes and humans: New interpretations based on the fossil great ape Dryopithecus. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 37: 11–63

Begun D.R. 2010. Miocene Hominids and the Origins of the African Apes and Humans. Annual Review of Anthropology 39:67-84

de Bonis, Louis and J. Melentis, J. 1977. Les primates hominoides du Vallesien de Macedoine (Grece): etude de la machoine inferieure. Geobias. 10: 849–855.

Fleagle 1999.

Gulec, Erksin S., et al. 2007. A new great ape from the lower Miocene of Turkey. Anthropological Science. 115: 153–158.

Harrison, T. 2012. Catarrhine Origins. In Begun, D. (ed.) A Companion To Paleoanthropology. Wiley Blackwell.

Ji, X-P et al. 2013. Juvenile hominoid cranium from the terminal Miocene of Yunnan, China. Chinese Science Bulletin, published online August, 2013

Koufos, George D and Louis de Bonis 2005. The late Miocene Hominoids Ouranopithecus and Graeceopithecus. Implications about their relationships and taxonomy. Annales de Paléontologie. 91: 227–240.

Leakey, L. and W. LeGros Clark 1951. The Miocene Hominoidea of East Africa. Fossil Mammals of Africa, vol.1. The Natural History Museum in London.

Pan, Ruliang; C. Groves,and C. Oxnard 2004. Relationships Between the Fossil Colobine Mesopithecus pentelicus and Extant Cercopithecoids, Based on Dental Metrics. American Journal of Primatology. 62 (4): 287–299.

Pilbeam, D. 1982

Simons, E. L and W. Meinel (1983). Mandibular ontogeny in the Miocene great ape Dryopithecus. International Journal of Primatology. 4 (4).

Villalta, J.F. and M. Crusafont 1944, Notas y Comunicaciones del Instituto Geologico y Minero de España.

Walker, A. and P. Shipman 2005. The Ape in the Tree. Harvard University Press.

XuePing Ji, Nina G. Jablonski, Denise F. Su, ChengLong Deng, Lawrence J. Flynn, YouShan You & Jay Kelley

2013 Juvenile hominoid cranium from the terminal Miocene of Yunnan, China. Chinese Science Bulletin volume 58, pages3771–3779(

Glossary