Athena Review Vol. 5, no. 1

Records of Life: Fossils as Original Sources

19. Permian Russia

Early Geologic mappings of western Russia

The geologic area from St. Petersburg to the Ural Mountains (an area now known as the East European Platform), flanked on the north by the Baltic and Berents Sea coastline, was first studied in detail in the early 19th century. The initial geological map of the region, made by Strangeways (1822), provided an important starting point although it contained innaccuracies. In the same period, the biologist Heinz Christian Pander (1830, 1856, 1857) made many important discoveries of Baltic marine fossils from the Silurian and Devonian periods.

Permian strata along the North Dvina River, which flows north into the White Sea at Arkhangelsk, were initially identified by the Scottish geologist Roderick Murchison in 1840-1. This came in the process of defining the geologic interval between the Carboniferous and Triassic as the Permian period, named after the ancient kingdom of Permia (Murchison et al. 1845).

Murchison had previously defined the Silurian period from fossiliferous strata in England and Wales, and then helped to identify the subsequent Devonian period (Murchison 1839). In the process, he was able to show that various fossils in the Devonian strata of Britain were equivalent to those recently described in Russia by Pander.

These included the lobe-finned fish Holoptychius nobilissimus, first defined by Louis Agassiz, now placed in the porolepiform order established by Swedish paleontologist Erik Jarvik. Although closer to lungfishes (Dipnoi) than to the direct ancestors of tetrapods, one genus of porolepiforms named Laccognathus, recently found in both Latvia and Ellesmere Island was apparently amphibious along rivers (see section on tetrapods for more details).

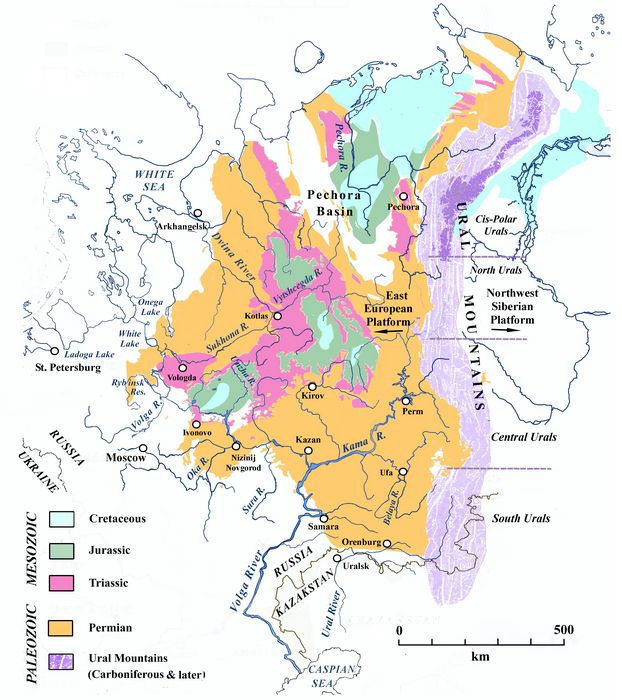

Fig.1: Map of Permian and Mesozoic geologic formations west of the Ural Mountains.

In 1840-1841 Murchison and two colleagues, E. de Verneuil and A. von Keyserling, and a Russian minerologist, Lieutenant Koksharof, explored the geological formations east of St. Petersburg and Moscow (Murchison et al. 1845). De Verneiul, a French expert on molluscs, had previously worked with Murchison on definining the Devonian sequence in the Rhine Valley.

One of the main Permian zones they encountered lay within the flat topography of Northwestern Russia, along the Dvinia River (fig.1). On ascending the Dvina River from Arkhangelsk, Murchison and his colleagues recognized Permian formations in riverbank exposures, sometimes comprising alternating layers of white gypsum and reddish or oxidized sandstone, representing riverine deposits overlying marine limestone strata. At this time, both marine and freshwater bivalve fossils were recovered by de Verneiul from the limestone layers (Murchison et al. 1845). In the 170 years since their initial definition of the Permian period, the fossil record of the Russian or East European block has been increasingly studied, and has provided one of the world's most important zones of evidence on paleozoic and mesozoic vertebrate evolution.

Permian faunal assemblages in Russia

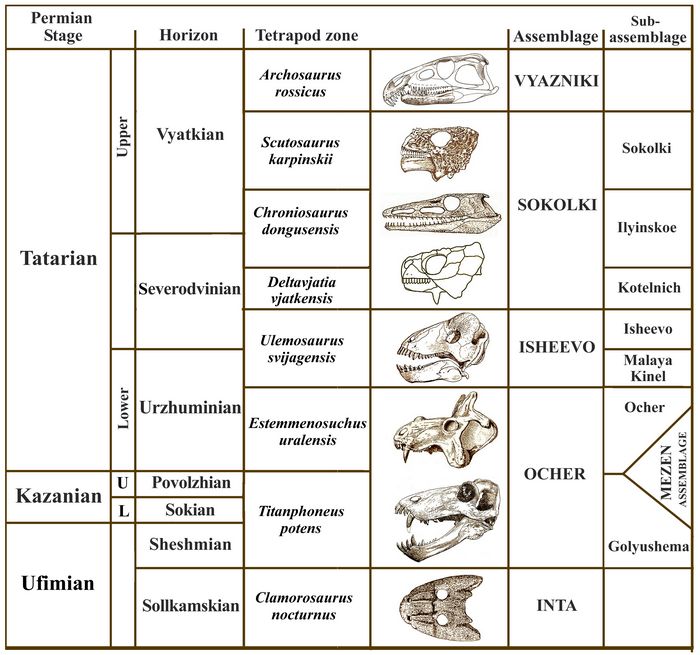

T

he

Permian in Russia is subdivided into three stages: Ufimian, Kazanian,

and Tatarian, which are further subdivided into horizons, tetrapod

zones, and faunal assemblages (fig.2).

he

Permian in Russia is subdivided into three stages: Ufimian, Kazanian,

and Tatarian, which are further subdivided into horizons, tetrapod

zones, and faunal assemblages (fig.2).The type sections of the Upper Permian are located in the eastern part of the Russian (East European) Platform and the Fore-Urals Trough in Tatarstan and Bashkortostan. In terms of overall geology, the Russian platform is underlain by a crystalline basement composed of Archean and Proterozoic rocks which are located at depths of 1500 to 2000 m and more. This is overlain by a sedimentary sheath composed (successively) of Devonian, Carboniferous, Permian, Jurassic, Cretaceous, Neogene and Quaternary rocks (Silantiev et al. 2013).

Fig.2: Permian Stages and Horizons in East European Russia, and their corresponding tetrapod zones and faunal assemblages (after Sennikov and Golubev 2005) .

Ufimian stage of the Permian

The Ufimian stage of the Permian is subdivided into two horizens, the Solikamskian and the Shemshian. The lowermost is named for the town of Solikamsk, located near Perm, in the trough along the Urals. Here the type section of this horizon contains Lower and Upper subformations.

The later, Sheshmian Horizon of the Ufimian Stage outcrops in the lower part of the banks of the Kama River (upstream of the mouth of the Vyatka River), and in the basin of the Shemsha River, from which it received its name. This horizon is largely composed of red-bed sandstones, which are usually recognized as alluvial formations. The Sheshmian Horizon is associated with the tetrapod Clamorosaurus nocturus, the type fauna for the Inta Faunal Assemblage (fig.2; cf. Sennikov and Golubev 2005).

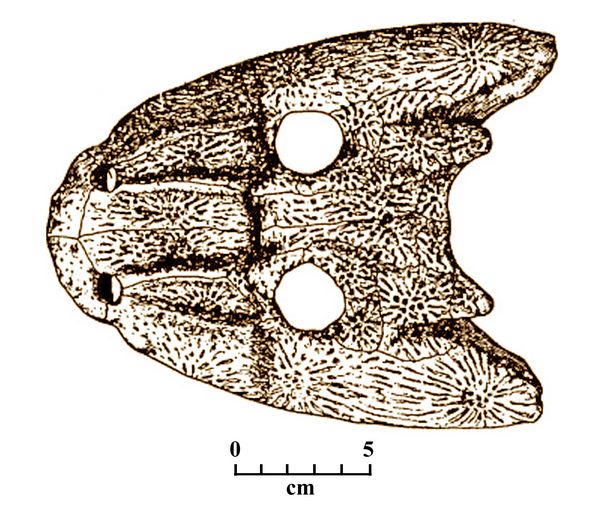

Clamorosaurus (fig.3) was a small temnospondyl amphibian about 23 cm (9

inches) long, dated at 273-272 mya. It was a member of the

Eryopidae family, named for the type genus Eryops, first

discovered in the Early Permian red beds of northern Texas (Cope 1882).

Besides its very wide, shield-shaped skull, Clamorosaurus has large

external nares or nostrils; both features are common to all

members of the Eryopidae family. Comparisons have often been made

between Eryopidae fossils found from the Ufimian stage of the Permian

in the Russian Block, and those in the North American Permian basins of

Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico, where Eryopidae are well represented

in the latest stages of the Early Permian.

Clamorosaurus (fig.3) was a small temnospondyl amphibian about 23 cm (9

inches) long, dated at 273-272 mya. It was a member of the

Eryopidae family, named for the type genus Eryops, first

discovered in the Early Permian red beds of northern Texas (Cope 1882).

Besides its very wide, shield-shaped skull, Clamorosaurus has large

external nares or nostrils; both features are common to all

members of the Eryopidae family. Comparisons have often been made

between Eryopidae fossils found from the Ufimian stage of the Permian

in the Russian Block, and those in the North American Permian basins of

Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico, where Eryopidae are well represented

in the latest stages of the Early Permian. Fig.3: Skull of Clamorosaurus seen from above, showing its wide profile and relatively large nostril openings, and the dermal scales which functioned as a protective surface on the skull.

.

Kazanian stage of the Permian

The

second stage of the Russian Permian, the Kazanian, begins with the

lower Sokian horizon (named for the Sok River) which mainly outcrops in

the eastern part of Tatarstan, along the Kama River.

The

second stage of the Russian Permian, the Kazanian, begins with the

lower Sokian horizon (named for the Sok River) which mainly outcrops in

the eastern part of Tatarstan, along the Kama River.Marine and lagoonal facies of the Upper Kazanian occur on the right bank of the Volga River, near the villages of Pechishchi, Naberezhye Morkvashi, and Krasnovidovo, while continental facies occur on the Kama River near the towns of Sheremetyevka and Sentyak.

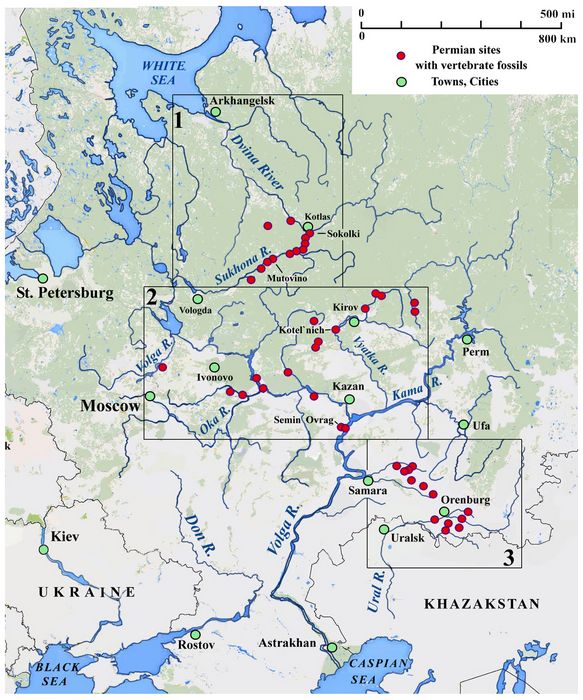

Fig.4: Middle and Late Permian sites along three river drainages in western Russia, including 1) the North Dvina River; 2) the Volga River; and 3) the Ural River (after Golubev 2000a, fig.6.).

Therapsids from Kazanian levels include a number from the Dinocephalian ("terrible head") suborder, whose fossils are widespread in Russia, China, Brazil, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Tanzania. Dinocephalians were large-bodied early therapsids that included herbivores, carnivores, and omnivores, some semi-aquatic and others terrestial. They were among the largest animals of the Permian period.

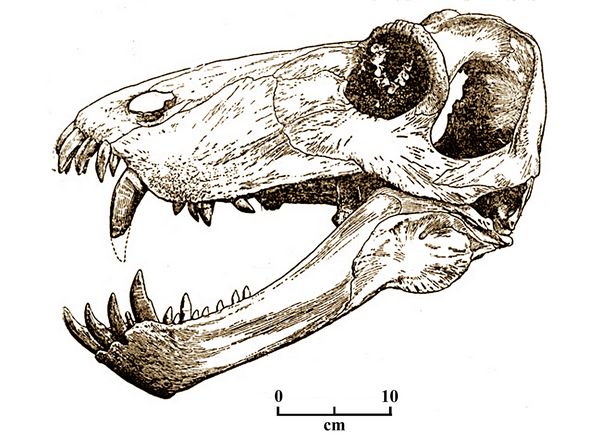

One prominent example is Titanophoneus ("titanic murderer"), a large carnivore dating from the Middle to Late Permian period (270-260 mya). The type species, T. potens, was found at Isheevo in the East European Platform in Russia (Efremov 1938). Titanophoneus (fig.5) had an adult body length of about 2.85 m and a skull length of 80 cm, with a heavy long snout. The long tail and short limbs show the species to be a primitive therapsid with a sprawling stance. The teeth are large, with twelve large palate incisors followed by two projecting canines and various smaller back teeth. The form of Titanophoneus retains similarities with those of earlier pelycosaur synapsids, such as Dimetrodon.

Fig.5: Skull of Titanophoneus potens (after Efremov 1938).

Tatarian stage of the Permian

The third and highest stage of the Permian, the Tatarian stage, represents a terrestial setting which was crossed by numerous rivers. This widespread stage, up to 200-250 m in thickness, is mainly exposed in in the watersheds of rivers, almost always overlying the eroded surface of the Kazanian. The Tatarian is composed of red-bed (variegated) clays, siltstones, sandstones, marls, dolomites, and limestones. These contain only non-marine fossils including bivalves, plants, insects, and vertebrates. The type sections are located outside Tatarstan, on the Vyatka River between the mouth of the Cheptsa River and the mouth of the Kobra River.

The Tatarian is subdivided into Lower, Middle, and Upper substages, corresponding with the Urzhuminian, Severodvinian, and Vyatkian horizons. These have extensive fossil deposits of terrestial flora and fauna, which will be explored in several site areas described below.

Today, about 170 years after the initial exploration of Permian deposits in Russia by Murchison et al. (1845), dozens of large Tatarian sites haved been mapped and intensely investigated along the drainages of the North Dvina, Volga, and Ural Rivers (fig.4, boxes 1-3). The Tatarian vertebrate fossils found west of the Urals have been grouped into several faunal assemblages (fig 2, and Golubev 2000a). The Middle-to-Late Tatarian phase, known as the Severodvinian Horizon, is defined on the basis of faunal assemblages from three highly productive sites including Kotel'nich, Ilyinskoe (Semin Ovrag), and Sokolki, together grouped as the Sokolki Assemblage. This is followed chronologically by the Vayazniki Assemblage, representing the very end of the Tatarian up to the Permian-Triassic extinction. Together these provide the Russian equivalent of the Middle to Late Permian, Pristerognathus through Dicynodon Faunal assemblages in South Africa, and are also comparable to the Rio de Rasto faunal assemblage in Brazil (Cisneros et al. 2005).

.

Middle Permian fossil deposits at Kotel'nich

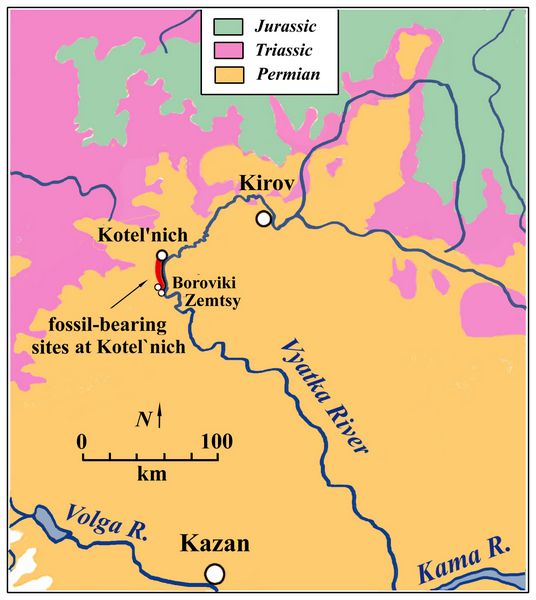

Along a relatively straight, south-flowing stretch of the Vyatka River,

about 80 km southwest of Kirov, significant Permian layers with

fossil deposits of an age corresponding to the Late Capitanian

stage are exposed near the town of Kotel`nich. These Middle

Permian red beds, composed of mudstones, siltstones, marl,

sandstones, and conglomerates, are exposed on the western bank of the

Vyatka river for 24 km between the towns of Kotel`nich and Zemtsy

(fig.7). The Vytaka River is a tributary of the Kama River, which, in

turn, is one of the main branches of the Volga River system. In

this area, the Vyatka has cut into an elevated escarpment of Permian

rocks, revealing outcrops up to 40 m high of horizontally banded red,

yellow, and brown sediments. These strata, comprising ancient riverine

deposits, have become one of the best known locations of tetrapod

fossils.

Along a relatively straight, south-flowing stretch of the Vyatka River,

about 80 km southwest of Kirov, significant Permian layers with

fossil deposits of an age corresponding to the Late Capitanian

stage are exposed near the town of Kotel`nich. These Middle

Permian red beds, composed of mudstones, siltstones, marl,

sandstones, and conglomerates, are exposed on the western bank of the

Vyatka river for 24 km between the towns of Kotel`nich and Zemtsy

(fig.7). The Vytaka River is a tributary of the Kama River, which, in

turn, is one of the main branches of the Volga River system. In

this area, the Vyatka has cut into an elevated escarpment of Permian

rocks, revealing outcrops up to 40 m high of horizontally banded red,

yellow, and brown sediments. These strata, comprising ancient riverine

deposits, have become one of the best known locations of tetrapod

fossils.Fig.7: Location map of the Kotel`nich Middle Permian deposits and geologic formations (after Benton et al. 2012)

Fossils from this area were first recorded by Krotov (1894, 1912), who, in mapping the regional geology, found isolated bones at a locality called Kotel'nich-1. Twenty years later, in 1933-5, several complete pareiasaur skeletons were discovered on the river bank just south of Kotel'nich. Comparing these findings with those known from Sokolki, Ephremov (1937, 1941) established two earlier complexes of dinocephalians, and a later pareiasaurian complex. In the 1990s, work led by D. L. Sumin from the Moscow Institute of Paleontology {PIN) recovered a wide variety of tetrapod skeletons, including dicynodonts, dromasaurs, therocephalians, and gorgonopsians, as well as pareiasaurs, of which 40 skeletons were found on the banks of the Vyatka, near the villages of Boroviki and Mukha. Excavations since 1992 at Port Kotel'nich have found numerous dicynodont skeletons.

The sequence at Kotel`nich dates from the middle Tatarian stage, in the Severodvinian Horizon. This includes two Tetrapod Zones, those of Deltavjatia vjatkensis and Chroniosaurus dongusensis (fig.2). Based on comparative stratigraphy and magnetostratigraphy, these correspond to the Late Capitanian stage of the Middle Permian in South Africa and elsewhere, dated at 263-260 mya (Benton et al. 2012).

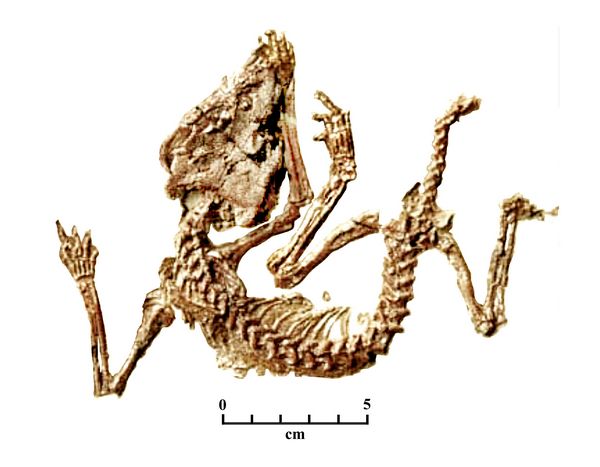

The main reptiles from the Kotel`nich outcrops include Deltavjatia (fig.8), large plant-eating pareiasaurs whose fossils are often found in groups. Also found are Suminia, an anomodont with unusually long arms, which may have been one of the first arboreal tetrapods. Other members of the Kotel`nich faunal assemblage are the gorgonopsian Viatkogorgon, the small insectivore parareptile Emeroleter (fig.9); and small carnivorous theriodonts (Benton et al. 2012).

Fig.8: Skeleton of Deltavjayia vjatkensis, a Middle Permian pareiasaur from the Kotel`nich deposits (after photo by Khlyupin in Benton et al. 2012, fig.13).

The nearby Port Kotel`nich locality also produced fossils of the dicynodont Australobarbarus, as well as two pareiasaurs. Another, somewhat later site in the immediate area, Sokol’ya Gora, has yielded the fish-eating chroniosuchian Chroniosaurus, the basal biomarsuchian Proburnetia, and the Pareiasaur Scutosaurus karpinski, the latter more commonly found in Late Permian deposits along the North Dvina river at Sokolki (Golubev 2000; Benton et al. 2012).

Equally well represented at Kotel'nich are small, carnivorous parareptiles of the Nycteroleteridae family, of which the type genus, Nycteroleter, means "night thief". Originally named by I.A. Efremov in the 1930s for their large eyes, suggesting night hunting, the family also includes the genera Emeroleter ("day thief"; fig.9), Macroleter ("large thief"), and Bashykroleter. Their body size is about 20-25 cm, with a relatively large skull 5-7 cm long. Recent excavations sponsored by the Vyatka Palaeontological Museum found two complete skeletons of Emeroleter, one adult and one juvenile, together in a fossil burrow (Khlyupin 2007).

Fig.9: Skeleton of Emeroleter (after Khlyupin 2007).

.

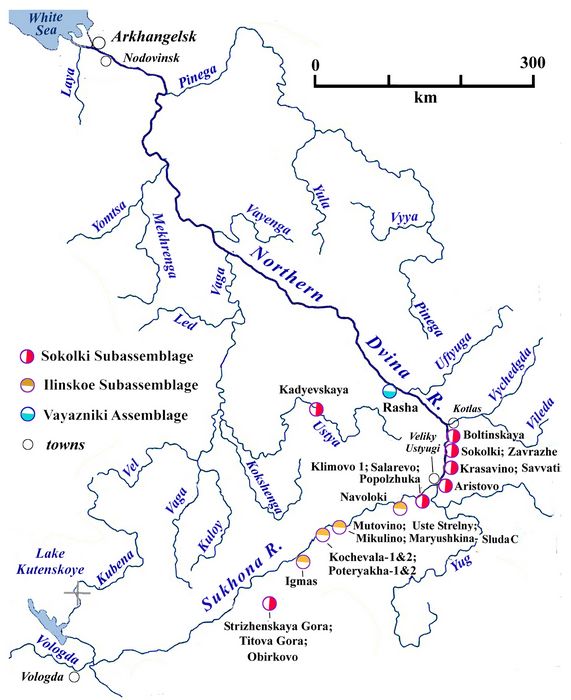

Late Permian fossil assemblages on the North Dvina River

In 1892, about the same time as the fossil beds of Kotel`nich were

first investigated, the Russian geologist Vladimir P. Amalitzky

examined large concretions found along the Northern Dvina River near

Kotlas (fig.10). These concretions were found to contain relativedly

well-preserved fossils of both land vertebrates and plants. With the

support of the Petrograd Society of Naturalists and the Russian Academy

of Sciences, Amalitzky and his wife Anna undertook excavations around

Kotlas between 1899 and 1914.

In 1892, about the same time as the fossil beds of Kotel`nich were

first investigated, the Russian geologist Vladimir P. Amalitzky

examined large concretions found along the Northern Dvina River near

Kotlas (fig.10). These concretions were found to contain relativedly

well-preserved fossils of both land vertebrates and plants. With the

support of the Petrograd Society of Naturalists and the Russian Academy

of Sciences, Amalitzky and his wife Anna undertook excavations around

Kotlas between 1899 and 1914.The Late Permian exposures along the Northern Dvina River comprise a series of thin, superimposed sandstone layers representing ancient river channel deposits. Within these sandstone layers, many fossils were found to be contained in the hard, limy concretions. Since these sometimes included whole skeletons as well as bone fragments, it was evident that the concretions had formed soon after the death of the animals, while the bones were still joined by ligaments. These cacoon-like concretions enabled unusual levels of preservation. Over 100 tons of fossil-bearing concretions were removed from the North Dvinian site.

Fig.10: Map of Late Permian sites along the Northern Dvina and Sukhona Rivers in western Russia. Most sites have either of two subassemblanges of the Sokolki Fauna (Solkolki and Ilinskoe), while another site (Rasha) has the later Vayazniki Faunal Assemblage (after Golubev 2000a, fig.6).

The Dvina River fossils were found to represent a rich variety of synapsids, reptiles, and amphibians, as well as freshwater mollusks, and plant fossils including Glossoptera. This Permian conifer is normally found only in southern latitudes of Gondwanaland, but its occurrence at various Late Permian sites on the Russian platform, such as those along the Dvina River, provides a well-known exception.

Vladamir Amalitzky died in 1918 and his wife Anne Amalitzky, who had drawn all the figures in the reports, edited six mss. on the paleontology and three on the geology of the North Dvinia sites. The first of these was published in two parts, one on Dvinisaurs and the second on Seymourians. A summary of the findings was also published in 1922 in the Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Amalitsky 1922). In 1922 at the Academy of Sciences in Petrograd, ten complete skeletons of pareiasaurs were exhibited, with two complete skeletons of the gorgonopsian Inostranzevia, and several skulls of Dicynodon, as well as skeletons of the primitive Seymouridae Kotlassia, the newly discovered amphibian Dvinosaurus, and various other vertebrate and plant fossils.

The North Dvina excavations revealed numerous remains of Late Permian

synapsids which parallel both in number and variety those found in the

Gondowan deposits of South Africa, as well as those known from Brazil,

Australia, Antarctica, India, and China. These include pareiasaurs,

gorgonopsians, anomodonts, therocephalians, and cynodonts. Each is

related to Late Permian fauna from equivalent faunal zones in the South

African Beaumont Formation and elsewhere.

The North Dvina excavations revealed numerous remains of Late Permian

synapsids which parallel both in number and variety those found in the

Gondowan deposits of South Africa, as well as those known from Brazil,

Australia, Antarctica, India, and China. These include pareiasaurs,

gorgonopsians, anomodonts, therocephalians, and cynodonts. Each is

related to Late Permian fauna from equivalent faunal zones in the South

African Beaumont Formation and elsewhere.The skeletal material of Kotlassia prima, a primitive Seymourian amphibian from the Upper Permian of the North Dvina, was relatively complete. Kotlassia is a terrestrial form, probably similar to Seymouria, in contrast to the contemporary Dvinosaurus (Bystrow 1944). More recent finds of related taxa in Khazakstan show they were amphibians and not primitive amniotes as once thought (Laurin 1996).

The pareisaurs of the Northern Dvinia region, represented by 13 skeletons, 30 craniums, and many other isolated bones, are smaller than those in the Karoo basin in South Africa, such as Bradysaurus. The Russian pareiosaurs are otherwise notable for the unique patterns of dermal scales or body armor on their exteriors. A prominent example is Scutosaurus karpinski (fig.11). This large animal, 2.45 m in length, had its back covered with star- shaped dermal plates, and its belly covered with small conical bosses.

Fig.11: Skull of Scutosaurus karpinskii seen from above and from the left side. The drawing shows intricate patterns of dermal scales serving as armor.

Theriodonts were represented by the large gorgonopsian Inostranzevia alexandri, of which two complete skeletons were found, their craniums 55 and 51 cm. long. These late gorgonopsians had extremely large, serrated canine teeth, as well as strong incisors, and conical molars, which were only in the upper jaw, the lower jaw lacking any molars (Amalitzky 1922).

Therocephalians were represented by the species Anna Petri (named for Anna Amalitzky), with two skulls lacking the lower jaws.The skull form was considered most similar to rhat of Scylacosaurus in South Africa (Broom), but with a broader and shorter cranium.

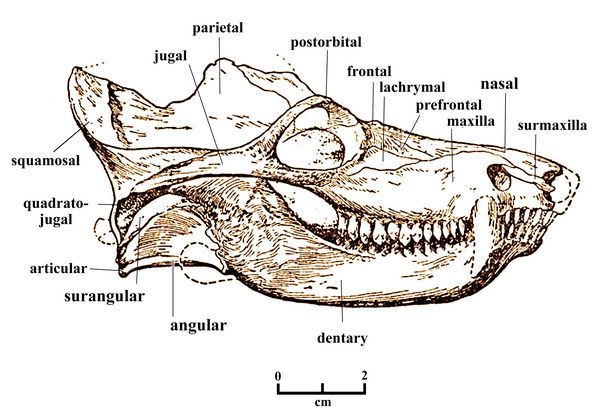

Cynodonts found at Sokolki include the stem mammal Dvinia prima (fig.12), a small to medium-sized carnivore with large upper canines, whose skull length was 7-10 cm. Dvinia, initially studied by P.P. Sushkin, was more completely defined by Tatarinov (1968). Dvinia is considered close to several South African forms from the Late Permian and Early Triassic, including Trithelodontia (Broom), Gomphognathus, Trirachodon, and Diademodon.

Fig.12: Skull of Dvinia prima, with bones labelled (after Tatarinov 1968).

Sushkin (1927) also noted features of the middle ear region of Dvinia. These otic features included a contact between the stapes and the paraoccipital process, and the presence of an opening called the foramen stapediale. Tatarinov placed Dvinia in the Procynosuchoid superfamily, and because of its distinct anatomy, Dvinia was placed within its own family, Dviniidae. Dvinia has advanced or transitional features of both the middle ear and a double set of both reptilian and mammalian jaw hinges (Tatarinov 1968, p.33).

References:

Amalitzky, V. P. 1922. Diagnoses of the new forms of vertebrates and plants from the upper Permian of North Dvina. Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg 16 (6), pp.329–340.

Benton, M.J., A.J. Newell, A.Yu Khlyupin, I.S. Shumov, G.D., Price, and A.A. and Kurkin 2012. Preservation of exceptional vertebrate assemblages in Middle Permian fluviolacustrine mudstones of Kotel'nich, Russia: stratigraphy, sedimentology, and taphonomy. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 319-320, pp.58-83

Betekhtina 1966. Upper Palaeozoic non-marine Pelecypoda (bivalves) of Siberia and Kazakhstan. Inst. geol. geofiz.,Akad. Nauk.

Bystrow A. P. 1944. Kotlassia prima Amalitzky. Geological Society of America Bulletin 55, pp.379-416.

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. WH Freeman & Co.

Cisneros, J.C., F. Abdala, and M.C. Malabarba 2005. Pareiasaurids from the Rio de Rasto Formation, southern Brazil: Biostratigraphic implications for Permian Faunas of the Parana Basin. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 8(1), pp.13-24.

Efremov, I. 1938. Some new Permian reptiles of the USSR, Comptes Rendus Acad. Sci. USSR. Paleontol., Vol 19, N 9.

Efremov, I.A. and B.P. Vyushkov 1955. Catalogue of localities of Permian and Triassic terrestrial vertebrates in the territories of the U.S.S.R. Trudy Paleontologicheskiy Instituta 46, pp. 1-185.

Golubev, V.K. 2000. The Faunal Assemblages of of Permian Terrestial Vertebrates from Eastern Europe. Paleontological Journal 34, suppl.2, pp. S211-S224.

Ivakhnenko, M. F. 1981. Discosauriscidae from the Permian of Tadzhikistan. Paleontological Journal 1981, pp.90-102.

Ivakhnenko, M. F. 2001. Tetrapods from the East European Placket—Late Paleozoic Natural Territorial Complex. Proceedings of the Paleontological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences 283, pp.1–200

Kashtanov, S.G. 1934. On the discovery of Permian reptiles on the River. Vyatka, near the town of Kotel`nich.. Priroda 1934 (2), pp. 74-75.

Klembara, J. 1995. The external gills and ornamentation of skull roof bones of the Lower Permian tetrapod Discosauriscus (Kuhn 1933) with remarks to its ontogeny. Paläontologische Zeitschrift 69, pp. 265-281.

Klembara, J. & M. Janiga. 1993. Variation in Discosauriscus austriacus (Makowsky 1876) from the Lower Permian of the Boskovice furrow (Czech Republic). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 108. pp. 247-270.

Krotov, P.I. 1894. Geological map of European Russia. Sheet 89. Trudy Geologicheskogo Komiteta 13 (2), pp. 1-228.

Krotov, P.I. 1912. The western part of the Vyatka Province. Sheet 89. Trudy Geologicheskogo Komiteta Novaya Seriya 64, pp. 1-128

Kuznetsov, V. V. & M. F. Ivakhnenko. 1981."Discosauriscids from the Upper Paleozoic in Southern Kazakhstan. Paleontological Journal 1981: 101-108.

Laurin, M. 1996. A reappraisal of Utegenia, a Permo-Carboniferous seymouriamorph (Tetrapoda: Batrachosauria) from Kazakhstan. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16 (3), pp.374-383.

Murchison, R. I., 1839. The Silurian System.

Murchison, R. I., E. de Verneuil, and A. von Keyserling, 1845. The Geology of Russia in Europe and the Ural Mountains. London, John Murray.

Newell, A.J., A. G. Sennikov, M. J. Benton, I. I. M Molostovskaya, V. K. Golubev, A.V. Minikh and M. G. 2010. Disruption of playa–lacustrine depositional systems at the Permo-Triassic boundary: evidence from Vyazniki and Gorokhovets on the Russian Platform, Journal of the Geological Society 167( 4) ,pp. 695-716

Pander, H.C. 1830. Beiträge zur geognosie des russischen reiches (Contributions to the geology of the Russian Empire).

Pander, H.C. 1856. Monographie der Fossilen Fische des silurischen Systems der Russisch-Baltischen Gouvernements (Monograph of fossil fish from the Silurian stratum of the Baltic regions), St. Petersburg.

Pander, H.C. 1857. Ueber die Placodermen des devonischen Systems (On placoderms of the Devonian system).

Pravoslavlev, P. A. 1927 . Gorgonopsidae from the North Dvinsky excavations of V. P. Amalitsky. Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Leningrad [St Petersburg].

Sennikov, A.G. and V.K Golubev 2005. Unique Vyazniki Biotic Complex of the Terminal Permian from Central Russia ...` in The Non-Marine Permian (ed. Lucas & Zeigler). New Mexico Mus. Nat.Hist & Science Bull.30..

Silantiev, V.V. et al. 2013. The Permian of European Russia. Kazan Geological Museum, Kazan, Russia.

Sushkin, P.P. 1929. Permocyadon, a Cynodont reptile from the Upper Permian of Russia. Proc. X Internat Congress Zoology, Budapest.

Tatarinov, L.P. 1968. Morphology and Systematics of the Northern Dvinia Cynodonts (Reptilia, Synapsida; Upper Permian). Yale University Postilla 126.

Glossary