|

Rumen Ivanov Novae

was a Roman legionary camp and early Byzantine town on the right

Danubian bank, located at the confluence of the small Derman Dere river

(figs.1,2). Today the site, named Staklen or Pametnitsite ("The Monuments")

lies 4 km east of the modern harbor town of Svishtov. The low cliffs

overlooking the Danube floodplain have been settled since the Late

Bronze Age. Burials from that period (both inhumation and cremation),

excavated east of the military camp, contained grave goods such as

pottery plates, pitchers, and cups. Materials dating to the Late Bronze

Age and to the Hellenistic period were also found beneath Tower no. 1

of the eastern extension of the Roman fort (Novae II). The combined

evidence suggests that a Thracian settlement must have existed in

pre-Roman times on both banks of the Dermen Dere. Archaeological research at Novae: In 1959 the Polish and the Bulgarian

Academies of Sciences planned joint archaeological excavations of an

ancient settlement in northern Bulgaria. Because of its historical

importance, they chose Novae. The Polish team includes members from the

Institute of Archaeology at the University of Warsaw and, after 1970,

the Institute of History at the University of Poznan. The Bulgarian

side is represented by the Institute of Archaeology and the Museum at

the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences and by the Museum of History in

Svishtov. Fig.1: Fig.12: The Peutinger Table (Tabula Peutingeriana),

a map of the Roman Empire originally dating from the 3rd century AD, is

now preserved in a 14th century copy. Novae is shown as Novas (arrow at right). North of the Danube is recorded a continuous belt of Sarmatian tribes (photo: Rumen Ivanov). A legionary camp was

built at Novae and garrisoned by legio VIII Augusta during the reigns

of Claudius and Nero (AD 45-68), but by AD 69 this legion had left

Moesia, with the camp then garrisoned by legio I Italica. After Moesia

was divided in AD 86 into Inferior and Superior parts, Novae and legio

I Italica played a significant role in the history of the province of

Moesia Inferior. Detachments from the legion were recorded in AD 134 in

the important inter-provincial center Montana, as well as in the North

Black Sea region. Legio I Italica and legio XI Claudia (whose base camp

had been established after Trajan’s Dacian Wars at Durostorum) took the

side of Septimius Severus (fig.6) in his struggle for the purple imperial cloak

of the Roman Empire.  In AD 170 the region of

Novae was invaded by the Costoboci. This tribe of north Thracian

(Dacian) origin was considered to have inhabited the area along the

valley of the Syretus River, a northern tributary of the Danube now in

southwest Romania. Fig.2: Fig.1: Novae and its environs (after L. Press and T. Sarnowski 1990). Beginning in AD 250 Lower

Moesia and Thrace suffered from waves of Gothic invasions, in which

Novae was captured and the towns outside the military camp (the

canabae and municipium) were destroyed. After this, the fort was

expanded with the addition of Novae II, and the civilian population

moved inside its stone walls. From the reign of Diocletian (AD 284-305)

on, Novae formed part of the new ly constituted province of Moesia

Secunda, whose provincial capital was Marcianopolis (modern Devnya in

the Varna district). ly constituted province of Moesia

Secunda, whose provincial capital was Marcianopolis (modern Devnya in

the Varna district). Fig.3: Fig.2: Plan of the Roman harbor facility north of the legionary camp’s porta praetoria. Nos. 1-7 show locations of stone remains of the installation (after T. Sarnowski 1996). In AD 376-378 the dioceses

of Dacia and Thrace were invaded once again by the Goths. This is

widely attested in late Roman and early Byzantine sources such as

Ammianus Marcellinus, Claudius Claudianus, Sextus Aurelius Victor,

Eusebius Hieronimus, and Jordanes (see bibliography). The recent

archaeological excavations prove that Novae was one of numerous

settlements in the Danubian region which suffered badly at the hands of

the Goths. Somewhat later burned layers have also been found in many

sectors of Novae, related to invasions by the Huns in the first half of

the 5th century.

By

AD 476 and 486-88, Novae was the principal residence of the Gothic king

Theodoricus (Prostko-Prostynski 1997; Marcelinus Comes, Chronicon 487,

X). As at other settlements along the south bank of the Danube, by the

end of the 6th and in the beginning of the 7th century, Novae was

exposed to constant attacks of Avars and Slavs. The latest ancient

coins from the site date to the Byzantine emperors Phocas and Heraclius

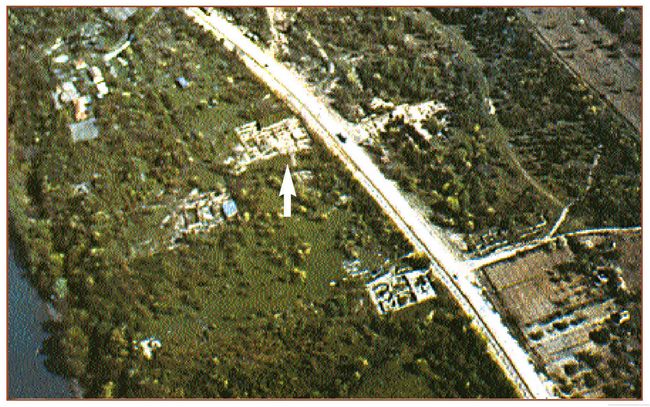

(between AD 603 and 613). Fig.4: Fig.3: Air photograph of Novae (arrow) on the south bank of the Danube river, at far left. View faces southeast (Anon., History of Bulgaria, Vol.1, Sofia, 1979).

Bulgarian glazed and painted pottery from the 12th-14th centuries AD

has been found in some sectors in Novae. A settlement, while as yet

poorly defined, definitely existed on the ruins of the antique city of

Novae during the Middle Ages.

Topography and

fortifications of the Roman site: Novae was built on a plateau

surrounded on the south and east by the small river Dermen Dere (about

20 km long) which flows into the Danube. The hilly terrain on the south

Danube bank slopes down from south to north, contrasting with the

northern Danube bank which is flat and marshy (fig.2).

The legionary camp at Novae, whose north side adjoined the south bank

of the Danube, occupied 17.7 ha. (fig.4). The rectangular plan of the

camp (castra) was 485 by 365 m, built in the classical proportion of 4

to 3 as described by Hyginus in Chap.32 of De munitionibus castrorum,

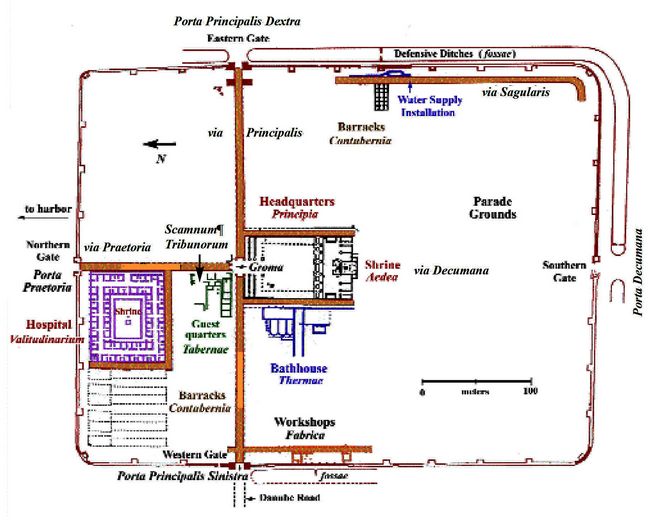

his 3rd century treatise on military camps. . Fig.5: Fig.4: Novae: Plan of the legionary camp (castra) during the 2nd - 3rd centuries AD (after T. Sarnowski 1998).

Outer

defenses of the camp: Remains of an early defensive ditch (fossa) have

been discovered from either Claudian or, more likely, Neronian

times (AD 54-68). During the later 1st century, this was upgraded by a

system of four defensive ditches, as revealed by T. Sarnowski of the

University of Warsaw’s Institute of Archaeology. Based on overlying

pottery and general site context, these constructions date to the

Flavian period (AD 69-96). The two largest fossae were V-sectioned

ditches measuring, respectively, 5.5 and 3.5 m wide, and 2.9 and 3.5 m

deep. Two smaller ditches in the eastern direction are U-sectioned, 2.3

and 3 m wide, and both 2 m deep. The distance from the camp’s rampart

(vallum) to the outermost ditch is 26 m, again corresponding to Roman

conventions of defense works (Johnson 1987). There is also a narrow

(0.5 m) berm between the rampart and the innermost ditches. At a later

time, these four Flavian-era fossae were replaced with two newer

ditches 14 and 10 m wide, and 4 and 3.5 m deep, separated by a berm of

2.5 m.

The legionary camp at Novae was initially

defended by earth-and-timber walls. Near the eastern rampart, T.

Sarnowski discovered a thick burnt layer, whose latest finds date to

Nero’s reign. The fire must represent the time of the Civil War in AD

68-69, when, according to Tacitus, the Lower Moesian defence system

sustained great damage from barbarian incursions (Historiae, 46, 79).

Five rectangular inner towers have so far been excavated at Novae.

These, probably from the later Flavian fortifications, were all built

of timber and are 3-6 m in diameter. Four lie along the eastern rampart

some 40-41 m apart, with the fifth tower in the southeastern corner.

Sections of the ramparts in front of these towers were faced with

adobe, while the lower part of the rampart was strengthened from the

inside by a few rows of stone blocks.

In

Trajan’s reign (AD 98-117), Novae’s fortifications were completely

rebuilt in stone, including a perimeter wall some 1.5-1.6 m thick,

apparently in opus vittatum (stone alternating with brick or

bonding tile layers). While opinions vary as to when this outer stone

wall was built, it was probably done between AD 103-105. The earlier,

Flavian rampart was partially incorporated in the new fortification

system, but its outer part had been cut through by the stone wall,

while the inner one was remodelled. A total of 40 stone towers were

also built, with those on the corners and middle placed on the inside,

while those flanking the gates projected slightly outside the wall.

Distance between the towers was 38-40 m along the longer walls, and

29-33 m along the shorter ones (P. Donevski).

Interior of the camp: Coming from the west, the

Roman road along the right bank of the Danube led to the western gate

of the camp (porta principalis sinistra). Excavations have revealed

four building periods dating from the Principate through Late

Antiquity. During the first period the west gate was flanked by two

slightly projecting solid towers (bastions) of an irregular,

quadrangular plan, both over six meters in diameter. The gate opening

is 8.15 m wide on the outside and 7.15 m inside.

The northern gate (porta praetoria) is poorly

preserved, with only parts of its s ubstructure surviving. A stone drain

leading north to the Danube bank has been unearthed under pavement of

the via praetoria. Architectural remains of a harbor installation have

recently been discovered very close to the northern gate (fig.2). A

variety of stamp types on bricks and tiles found in Novae include

representations of river ships (fig.11). ubstructure surviving. A stone drain

leading north to the Danube bank has been unearthed under pavement of

the via praetoria. Architectural remains of a harbor installation have

recently been discovered very close to the northern gate (fig.2). A

variety of stamp types on bricks and tiles found in Novae include

representations of river ships (fig.11).

Fig.6: Fig.5: Bronze fish appliques, from the western aerarium near the shrine of the principia or headquarters (after L. Press and T. Sarnowski 1990). While

the eastern gate (porta principalis dextra) has been only partly

excavated, the course of the via principalis was unearthed in its

vicinity. The southern and western gates (porta decumana) are similar

in plan (fig.6), and are flanked by two irregular,

quadrangular towers, whose sides measure about 5 m and project slightly

on both sides of the wall. The western gate is flanked by bastions,

while the southern has thin-walled towers. Through the camp ran two main streets, the via praetoria (North-South)

and the via principalis (East-West), whose courses have been closely

determined. The better defined via praetoria, some 6.8 m wide in the

1st and 2nd centuries, was narrowed slightly in the 3rd century to 6.1

m. It was flanked on both sides by sidewalks 1.6 m wide, separated from

the street by roofed and columned porticoes of the Ionic order. During

the earliest stage of construction in the latter half of the 1st

century, all the streets in Novae were covered with a layer of tightly

packed yellow soil. Later, they were paved with stone slabs. Fig.7: Fig.6 Novae -the principia or headquarters during the reigns of Trajan (phase II) through Septimius Severus and Caracalla (Phase III) (T. Sarnowski 1991). The presumed breadth of the via principalis was about 6 m. A small

section of another street measuring 3.4 m wide has been revealed near

workshops in the western part. Excavations in the southeastern side of

the camp also came upon a section of via sagularis, which proved to be

4 m broad.

Principia: The headquarters building

(principia legionis) lay at the crossroads of the camp’s two main

streets, the via praetoria and via principalis (fig.4). While little is

known about the camp’s headquarters used by legio VIII Augusta (AD

45-69), its principia seems to have been made of timber and to have

occupied roughly the same area as the later building. The earliest

building in stone during the Principate ( phase I) dates to Flavian

times, after legio I Italica was garrisoned at Novae at the end of AD

69. The second phase dates to the reign of emperor Trajan (AD 98-117),

and the third to the periods of Septimius Severus (AD 193-211) and

Caracalla (AD 211-217). A marble head of Caracalla (fig.7; also cover),

plus many dedicatory inscriptions, bronze appliques (fig.5), and coins

have been found in the principia. phase I) dates to Flavian

times, after legio I Italica was garrisoned at Novae at the end of AD

69. The second phase dates to the reign of emperor Trajan (AD 98-117),

and the third to the periods of Septimius Severus (AD 193-211) and

Caracalla (AD 211-217). A marble head of Caracalla (fig.7; also cover),

plus many dedicatory inscriptions, bronze appliques (fig.5), and coins

have been found in the principia. Fig.8: Fig.7: Marble head of the emperor Caracalla (AD 211-217) from the headquarters building at Novae (L. Press and T. Sarnowski 1990). The principia

of Phases II and III (fig.6) was a rectangular complex measuring 59 by

105 m (6100 m2). A north entrance led through a long, narrow

antechamber into a rectangular inner courtyard with porticoes on three

sides. Behind the colonnade were the arms depots (armamentaria) of the

legion. The courtyard was adjoined on the south by a narrow

cross-shaped hall (basilica), built in the time of Trajan, where

meetings of the military commanders were held. Eventually, stone rostra

were placed in both ends of the hall, with a set of four steps leading

to each. In later decades up to the reign of Commodus (AD 180-192), a

row of seven rooms was added behind the basilica in the south end of

the principia. The central room, projecting out from the south facade

and with a floor slightly higher than the basilica, served as the

shrine of the military standards (aedes or sacellum). On either side of

the shrine were small rooms (aeraria) for money and other valuables.

In front of the entrance into the principia was a stone groma or

gateway hall, whose four arches joined into a single structural body.

An inscription fragment of ANTO and bricks and tiles with stamps

LEG(ionis) I ITAL(icae) ANT(oninianae) have been found among its ruins.

These inscriptions to Antoninis (referring to either Caracalla or

Elegabalus) enable the groma to be dated to AD 212-222.

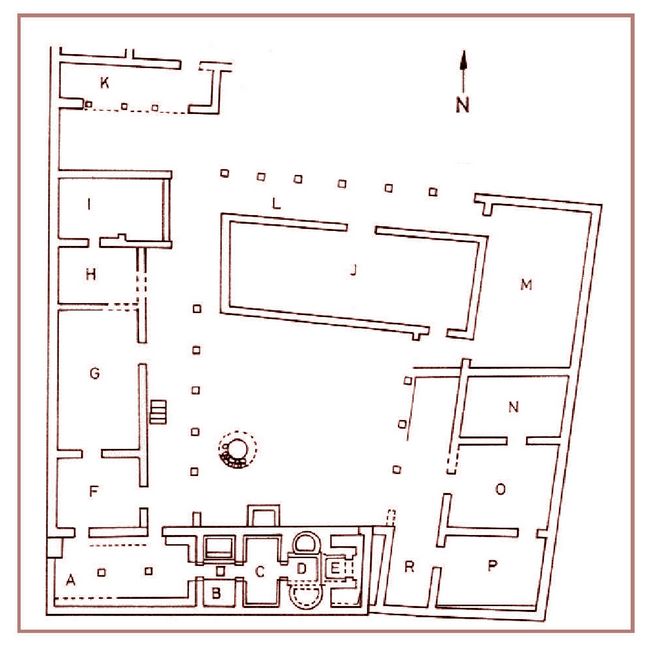

Scamnum tribunorum: Just north of the principia and northwest from the

crossroads of the main streets is a sector identified as the tribunal

quarters (scamnum tribunorum; fig.8). Recent excavations by a team of

Bulgarian archaeologists led by A. Milcheva and E. Gencheva show that

here, at first, were temporary barracks (contubernia) of legio VIII

Augusta, followed by timber barracks erected in two consecutive

building phases (stone barrack construction at Novae began only in late

Flavian times). The street façades were then remodelled, with special

quarters built for officials and guests (tabernae). Under Trajan the

tabernae were dismantled and replaced by the complex of the scamnum

tribunorum. phases (stone barrack construction at Novae began only in late

Flavian times). The street façades were then remodelled, with special

quarters built for officials and guests (tabernae). Under Trajan the

tabernae were dismantled and replaced by the complex of the scamnum

tribunorum. Fig.9: Fig.8: Novae - building phases I and II in the scamnum tribunorum (Milcheva and Gencheva 1991). Here a large sructure (1600 m2)

served as a residence for a high-ranking officer of legio I Italica. A

street separated this building from another to the west. The residence

is of the Italian city villa type, and consists of a number of rooms in

separate structures grouped around a central courtyard. At the

beginning of the 3rd century, the main entrance from the west had a

portico. This led into a vestibule, accessing three spacious rooms with

polychromatic mosaic floors and an underground heating installation

(hypocaustum). A bath was in the building’s southern wing, while a

kitchen occupied the northern one. A reconstruction took place during

the reign of Severus (AD 193-235), but the building was then destroyed

in t he Gothic invasions in the mid-3rd century. he Gothic invasions in the mid-3rd century.

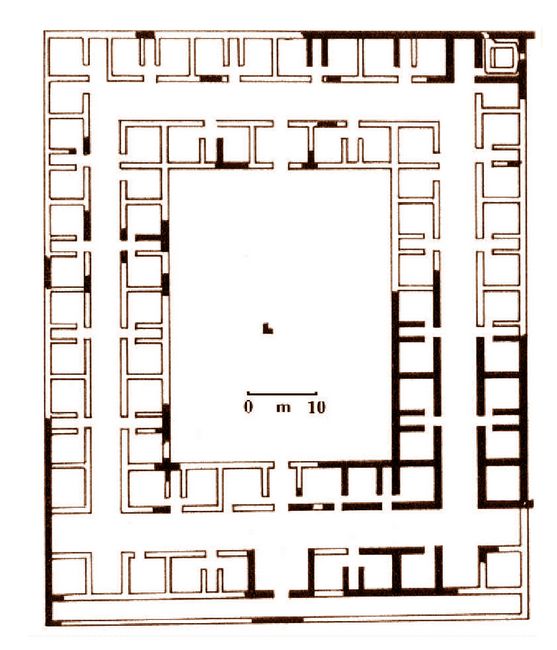

Valetudinarium: North of the scamnum tribunorum was the legionary

hospital or valetudinarium (fig.9), excavated by L. Press and P. Dyczek

from Warsaw University (1990). Begun during Trajan’s reign, the

hospital was completed by the mid-2nd century, and probably functioned

until the reign of Caracalla (AD 211-217). Tiles (tegulae) have been

found during the excavations with stamps of three legions, including

the I Italica, XI Claudia, and I Minerva. Fig.10: Fig.9: Novae’s valetudinarium (after L. Press and T. Sarnowski 1991).

The

hospital building is almost square, measuring 81.9 by 72.9 m. Its

eastern façade facing the via praetoria had a portico which led to the

main entrance. The valetudinarium building was composed of small

interconnected rooms surrounding a square inn er courtyard (42.4 by 42.6

m) which was encircled by a portico. In the middle of the courtyard

rose a small (4 m2) shrine (sacellum) devoted to the healing deities

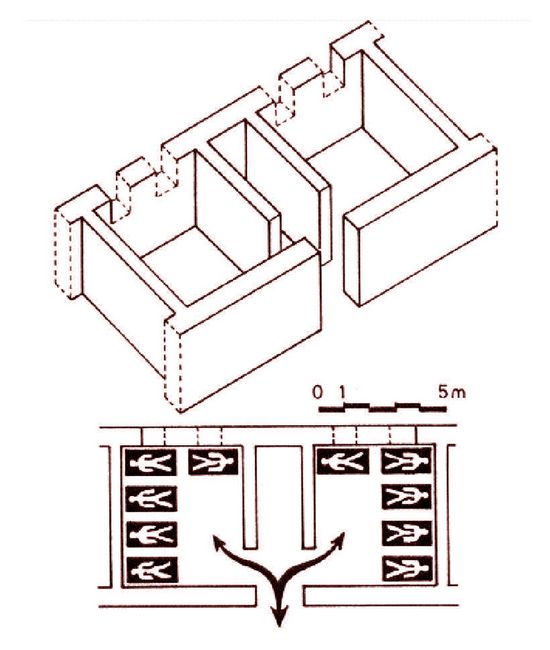

Asclepius and Hygia. Rooms (each 5 m2) were grouped into pairs

separated by an entrance hall (fig.10). Provided with a water-supply

and drain system, the hospital also had a big latrine in its northwest

corner. The barracks (contubernia) west of the valetudinarium were

probably built after the latter had ceased functioning. Barracks

have also been discovered and partially excavated south of the eastern

camp gate of Novae (B. Sultov, M. Chichikova). er courtyard (42.4 by 42.6

m) which was encircled by a portico. In the middle of the courtyard

rose a small (4 m2) shrine (sacellum) devoted to the healing deities

Asclepius and Hygia. Rooms (each 5 m2) were grouped into pairs

separated by an entrance hall (fig.10). Provided with a water-supply

and drain system, the hospital also had a big latrine in its northwest

corner. The barracks (contubernia) west of the valetudinarium were

probably built after the latter had ceased functioning. Barracks

have also been discovered and partially excavated south of the eastern

camp gate of Novae (B. Sultov, M. Chichikova).

Fig.11: Fig.10: A pair of rooms in the valetudinarium (after L. Press and T. Sarnowski 1990).

Baths: Bathing facilities were an integral part of Roman military camps

(see also AR 1, nos. 1,2, and 4). At Novae, beneath the foundations of

the valetudinarium was discovered the remains of a private military

bath (balneum). While its excavation has been very difficult, due to

the great depth of its remains beneath the massive later structures, it

has been established that the balneum was built and used in Flavian

times. Entered on the northern side, it had two rooms with heating

installations, each of them 11 by 15 m, as well as a pool for cold

water. Two semicircular niches (excedrae), each 5 m in diameter,

project outside one of the walls. Their floors were once covered with

polychrome mosaics. Another room, 14 by 7 m, has been partially

excavated in the southern part of the bath. A

larger bath building (thermae) for public bathing lay about 20 m west

of the principia (fig.4). This was probably used by legio I Italica

from the mid-2nd century until the Gothic invasions in AD 250-251. In

Late Antiquity, new s tructures were built on its ruins. The public bath

has not been fully excavated, but it has been established that the

caldarium or warm room, heated by hypocausts, ended with two

semicircular excedrae in the east. A rectangular pool measuring 9.73 by

6.53 m was built in the frigidarium (cold room) of the bath. At one

time there were stone seats along its sides. Three steps led down to

the 94 cm deep pool, whose bottom was paved with bricks, some bearing

the stamps of legio I Italica (fig 12). tructures were built on its ruins. The public bath

has not been fully excavated, but it has been established that the

caldarium or warm room, heated by hypocausts, ended with two

semicircular excedrae in the east. A rectangular pool measuring 9.73 by

6.53 m was built in the frigidarium (cold room) of the bath. At one

time there were stone seats along its sides. Three steps led down to

the 94 cm deep pool, whose bottom was paved with bricks, some bearing

the stamps of legio I Italica (fig 12). Fig.12: Fig.11: Bricks with stamps of legio I Italica representing river ships (after T. Sarnowski and J. Trynkowski 1986).

Canabae and Municipium: Outside the camp’s walls, the residential

villages (canabae) for veterans of legio I Italica and their families,

as well as artisans, craftsmen, and shopkeepers lay to the northwest,

west and southwest (fig.1). Northwest of the western camp gate, a large

building with an interior, peristyle courtyard is currently being

excavated by M. Chichikova and P. Vladkova, with 1800 m2 already

uncovered. Two limestone pedestals with Latin inscriptions were found

in the antechamber. Of these, the better preserved reveals dates (AD

240-244) and official titles of a person of senatorial descent (legate

of legio I Italica from AD 240-242, and proconsul of Sicily from

242-244). Given that fragments of bronze statues of men were also

found, the excavators suggest that the building was used by the

legionary legate. According to T. Sarnowski, however, it was a

residence intended for visits by high-ranking officials. Near this

building was placed the terminus of the aqueduct (castellum aquae) of

Novae.

Religious temples: A few hundred meters

from the southwest corner of the legionary camp, a shrine devoted to

Mithras was discovered in the territory of the canabae (fig.1). This

Mithraeum was in use from the 2nd century through the mid-3rd century.

Slightly later, under the emperor Aurelian (AD 270-275), a shrine

devoted to Sol Invictus and Sol Augustus was built at the same place.

Some 2.5 km to the southwest is a shrine devoted to Dionysius, god of

the theater and wine .

The area of Ostrite mogili

(“The Pointed Tumuli”) is situated 2.5 km east of Novae (fig.2). A

great number of architectural details and abundant archaeological

materials (coins, pottery, small finds) have been collected from the

surface there so far. The site has been identified with the municipium

or public town of Novae by Profs. B. Gerov and P. Donevski.

The canabae and the municipium did not survive the Gothic invasions in

the mid-3rd century and ceased to exist by that time. At the end of the

3rd century or a little later, an eastern extension of Novae was built

(now called Novae II). From that time onward during the late Roman era

of the 4th-6th centuries AD, the civilian population at Novae settled

within the walls of the expanded military camp. Fig.13: Late antique peristyle building at the place of the former valetudinarium (after L. Press and T. Sarnowski 1990). Novae II: In the 1960s and early 1970s, Bulgarian archaeologists

studied the fortification system of the later, eastern extension of

Novae designated as Novae II. This walled zone added 10 ha to the camp,

making a total enclosed area of 28 ha (fig.14). Due to the presence of

modern buildings and private vineyards, no excavations have been

carried out within the grounds of Novae II. Based on the excavation of

nearby pottery kilns and workshops, however, a craft quarter probably

existed there during the 1st through 3rd centuries AD. Examination of about 340 m of the eastern precinct wall and four

projecting towers (fig.14; tower nos. 1-4) showed the wall (preserved

only in its substructure) averaged 1.6 m thick. No gates were found

along its course, with the eastern gate probably obliterated at the end

of the 19th century during the construction of the new paved road from

Svishtov to Rousse, which passed across the site.

Fig.14: Plan of Novae showing its eastern extension (Novae II) in the late Roman and early Byzantine periods (4th-6th c. AD)

1. Central building; 2. Cathedral; 3. Basilica minor; 4. Bath and

bishop’s residence; 5-6. Small basilicas in the area of the former

scamnum tribunorum; 7. Peristyle villa; 8. Horreum; 9. Small basilica (after T. Sarnowski 1999).  All the towers on the eastern wall of Novae II are rectangular in plan.

The northernmost (tower no. 1; fig.15), situated close to the bank of

the Danube, measures 9 by 8.1 m externally, and 5.9 to 5.8 m on the

inside. Beneath its foundations was discovered an earlier paved street

leading from Novae I to the river bank. All the towers on the eastern wall of Novae II are rectangular in plan.

The northernmost (tower no. 1; fig.15), situated close to the bank of

the Danube, measures 9 by 8.1 m externally, and 5.9 to 5.8 m on the

inside. Beneath its foundations was discovered an earlier paved street

leading from Novae I to the river bank.

Fig.15: Novae II, tower no. 1 (after M. Chichikova 1967).

Tower no. 3, whose outside dimensions are 9.6 by 8

m, lies 147 m to the southwest of tower no. 1. Initially there was only

a postern between them, but later a new tower (no. 2) was added to the

wall at that midpoint location. The southeast corner of Novae II was

defended by a fourth tower (fig.16). At some point during the late

Roman period, a new, thinner wall of a similar construction was built

against the existing wall of Novae II. Except for a small section near

tower no. 4, where it is on the inside, all along its course it was

attached to the outside of the earlier wall. Tower no. 3, whose outside dimensions are 9.6 by 8

m, lies 147 m to the southwest of tower no. 1. Initially there was only

a postern between them, but later a new tower (no. 2) was added to the

wall at that midpoint location. The southeast corner of Novae II was

defended by a fourth tower (fig.16). At some point during the late

Roman period, a new, thinner wall of a similar construction was built

against the existing wall of Novae II. Except for a small section near

tower no. 4, where it is on the inside, all along its course it was

attached to the outside of the earlier wall. Fig.16: Novae II, tower no. 4 (after M. Chichikova 1965).

Along the better preserved southern wall of Novae II are tw o towers,

nos. 6 and 7, the former 7.15 by 6 m in exterior dimensions (fig.17).

About 50 m southwest of tower no. 6 is a gate tower which (like tower

7) projects on both sides of the wall, but the design in this case was

prompted by the displacement of the terrain. Near the gate-tower, the

wall, constructed in opus incertum (concrete and rubble core masonry),

is preserved to a height of 4 m. o towers,

nos. 6 and 7, the former 7.15 by 6 m in exterior dimensions (fig.17).

About 50 m southwest of tower no. 6 is a gate tower which (like tower

7) projects on both sides of the wall, but the design in this case was

prompted by the displacement of the terrain. Near the gate-tower, the

wall, constructed in opus incertum (concrete and rubble core masonry),

is preserved to a height of 4 m.

Fig.17: Novae II, tower no. 6 (after B. Sultov 1964). Tower no. 7, of

particular interest for its building chronology, measures 8.3 by 7.7 m

externally and 5 by 4.5 m on the inside. Tower 7 is not joined to the

wall, and projects on both sides. Originally built in the time of

Diocletian (AD 284-305) as one of a series of projecting rectangular

towers, it was later transformed under Constantine the Great (AD

306-337) into a detached U-shape, as the fortification system of Novae

I continued to undergo considerable changes. Later building activities

dating to the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (AD 527-565)

have been uncovered at the western gate of Novae I. In early decades of

the 6th century, both flanking towers were lengthened to the west and

the gate opening was remodelled from one entrance to two. However,

shortly after the mid-6th century the northern entrance was blocked.

It has been established that the principia functioned as military

headquarters until the mid-5th century. Dated building phases at Novae

from the Late Roman period are correlated in the area of the legionary

principia as follows: phase III/2 lasts from Emperor Macrinus (AD

217-218) to AD 316-317 in the mid-reign of Constantine I; phase IV to

the end of the 4th century; and phase V (the latest military period) to

ca. AD 450. The two final phases were civilian in nature: phase VI/1,

lasting to the time of emperor Justinian I; and phase VI/2, from Justin

II (AD 565-578) to the beginning of the 7th century. It has been established that the principia functioned as military

headquarters until the mid-5th century. Dated building phases at Novae

from the Late Roman period are correlated in the area of the legionary

principia as follows: phase III/2 lasts from Emperor Macrinus (AD

217-218) to AD 316-317 in the mid-reign of Constantine I; phase IV to

the end of the 4th century; and phase V (the latest military period) to

ca. AD 450. The two final phases were civilian in nature: phase VI/1,

lasting to the time of emperor Justinian I; and phase VI/2, from Justin

II (AD 565-578) to the beginning of the 7th century.

Fig.18: Late building phases of the scamnum tribunorum site in the 4th and 5th c.AD (after A. Milcheva and E. Gencheva 1991).

Extensive building activities reflecting change from military to

civilian uses are recorded in the area of the scamnum tribunorum or

tribune’s quarters (fig.18). A large structure with an inner courtyard

was built there in the time of Constantine I, remaining in use until

the reign of Valentinian I (AD 364-375). By in the beginning of the 5th

century, a small Christian basilica was erected in the northern part of

the area. A new workshop also appeared there at that time, but closer

to via principalis. Yet another small basilica was built in this sector

in the 6th century, along with one outside the walls (extra muros;

fig.21).

In the 4th century a rectangular (37 by

34 m) structure was built on part of the ruins of the valetudinarium

(fig.13). Its inner courtyard measured 23 to 16 m, w ith porticoes on

the eastern and western sides. There was a small bath consisting of

apodyterium (dressing room), frigidarium (cool room), tepidarium (warm

room), and caldarium (hot room) in the southern part of the building.

The praefurnium was built in the courtyard north of the bath. This

building is believed to have been the home of a wealthy citizen of

Novae. ith porticoes on

the eastern and western sides. There was a small bath consisting of

apodyterium (dressing room), frigidarium (cool room), tepidarium (warm

room), and caldarium (hot room) in the southern part of the building.

The praefurnium was built in the courtyard north of the bath. This

building is believed to have been the home of a wealthy citizen of

Novae. Fig.19: The complex of the bishop’s basilica and residence (photo: P. Namiota; A. Biernacki 1997).

Northwest of the residence just described,

a grain storehouse (horreum) was built and functioned in the 4th

century AD. Gradually it fell into ruin, and modest stone and clay

dwellings appeared at its place during the 5th to 6th centuries.

Immense late Roman construction was also carried out in the area of the

old legionary thermae. A new bath building was erected on their ruins

by the end of the 3rd or in  the beginning of the 4th century. This

consisted of a variety of rooms with different functions, only some of

which have been excavated so far (the caldarium, the tepidarium, and

part of the apodyterium, as well as two praefurnia). The entire bath

measures 20.76 by 16.7 m. Remains of a residential building were

discovered to the east. the beginning of the 4th century. This

consisted of a variety of rooms with different functions, only some of

which have been excavated so far (the caldarium, the tepidarium, and

part of the apodyterium, as well as two praefurnia). The entire bath

measures 20.76 by 16.7 m. Remains of a residential building were

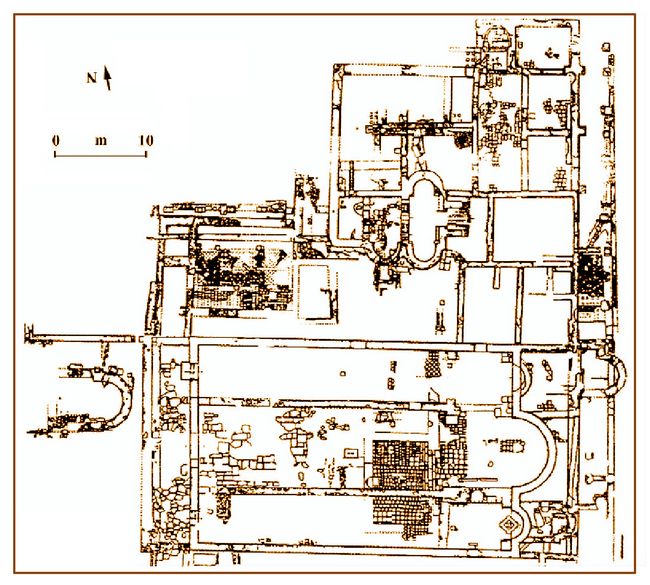

discovered to the east. Fig.20: Plan of bishop’s basilica, showing area of fig.19 (after A. Biernacki and S. Medeksza 1995). Since 1990, a bishop’s

basilica (figs.19,20), one of the largest such early Christian churches

on the Middle and Lower Danube, has been excavated by A. Biernacki

south of the bath. During the investigations between1990 and 1994, four

main building periods were established. The first structure, dating

from the last quarter of the 5th century AD, was a three-aisled,

single-apsed basilica. This was later rebuilt as a basilica of similar

form, with a narthex and apsed room (baptisterium or martyrium) built

against the east end of the southern wall. In the third (early 6th

century) phase, a three-aisled, three-apsed basilica evolved. This had

a widened narthex and totally remodelled naos, or central hall of the

basilica, containing a marble chancel-screen and two isol ated rooms

intended for priestly functions of protesis and deaconicon. The fourth

and last building phase from the late 6th century added to the

three-aisled, three-apsed basilica with a widened narthex, and an inner

baptisterium in the southeast corner of the southern aisle. ated rooms

intended for priestly functions of protesis and deaconicon. The fourth

and last building phase from the late 6th century added to the

three-aisled, three-apsed basilica with a widened narthex, and an inner

baptisterium in the southeast corner of the southern aisle.

Fig.21: Basilica extra muros ( M. Chichikova 1994). Archaeology has revealed distinct historic

stages in the rebuilding and transformation of Roman military

structures at Novae during the late Roman and early Byzantine periods.

The architecture of its early basilicas also reveals striking patterns

of both long-term cultural continuities and change.

.

Early sources on Novae

Claudius Ptolemaeus first lists the settlement “Noouai” in his 2nd

century AD Geographia (III,10,5). The 3rd century Antonine Itinerary

points out Novae as seat of the legio I Italica (Novas, leg. I Ital.;

221, 4).

In the early Byzantine era, the

Chronikon of Marcellinus Comes (487, X) tells of the Gothic king

Theodoricus burning down many settlements and returning after that “to

the Moesian settlement of Novae.” The 6th-century Gothic historian

Jordanes (Getica, 100-103) records the settlement under two names

(Euscia and Novae). A variant, Nóßaç, is also mentioned in

Theophylactus Simocatta’s Historiae (VII, 1, VIII, 3), in connection

with the campaigns of Peter, the brother of emperor Mauricius.

Notice is also given of Nóßai among the seven cities of the province

of Moesia Secunda, in Hieroclis’ Synecdemus (636, 6;

written AD 527-528). The city (civitas) of Nobas Italica also appears

in Book IV, chapter 7 of the anonymous 7th century Ravenna Cosmography.

References:

Donevski,

P. 1996. “Some Aspects of Defensive System of the Roman Camp Novae

(Moesia Inferior) in 1st-3rd Century.” Roman Limes on the Lower Danube.

Archaeological Institute, Belgrade, Cashiers des Portes de Fer,

Monographies 2, 201-203.

Dyczek, P. 1994. Sprawozdania z badan Institutu archeologii U. W. Warszawa, 15-17.

Dyczek, P. 1997. “New Late Roman Horreum from Sector IV at Novae.” in Biernacki (ed.) op.cit. 87-94.

Gentschewa,

E. 1999. “NeueAngaben bezueglich des Militaerlagers Novae im

Unterdonaubecken aus der frühen Kaiserzeit.” Archaeologia Bulgarica,

III, Sofia, 21-33.

Gerov, B. 1963. “Die gotische Invasion in

Mösien und Thrakien unter Decius im Lichte der Hortfunde.” Acta antique

Philippopolitana. Serdicae, 128-146.

Gerov, B. 1964. “Die

Rechtstellung der untermösischen Stadt Novae.” Akten des 4.

Internationalek Kongress für griechische und lateinische Epigraphik.

Graz-Wien-Köln, 128-133.

Gerov, B. 1977. “Zum Problem der Entstehund der römischen Städte am Unteren Donaulimes.” Klio, 59, N° 2, 299-309.

Gerov, B. 1977. “Die Einfälle der Nordvölker in den Ostbalkanraum im Lichte der Münzschatzfunde, I (101-284).” ANRW, II, 6.

Ivanov,

R. 1993. “Zur Frage der Planung und der Architektur der römischen

Militärlager.” Bulgarian Historical Rewiev, Sofia, No 1, 3-26.

Ivanov,

R. 1996. “Der Limes von Dorticum bis Durostorum (1-6 Jh.). Bauperioden

des Befestigungssystems und archäologische Ergebnisse 1980-1995.”

(Roman Limes on the Middle amd Lower Danube). Cahiers des Portes de

Fer, Monographies 2. Belgrade, 161-171.

Ivanov, T. 1971. “Zum Problem der Errichtung der Legio I Italica.” Roman Frontier Studies, 1967. Tel Aviv, 176-180.

Ivanov,T.

1974. “Die letzten Ausgrabungen des römischen und frühbyzantinischen

Donau-Limes in der VR Bulgarien.” in Actes du IXe Congrès International

d’Etudes sur les frontiéres romaines. Mamaia, 1972.

Bucuresti-Köln-Wien, 55-69.

Johnson, Anne. 1987.

“Verteidigungsanlagen eines Kastells mit Rasensodenmauer - Effektive

Speerwurfwite 25-30 m.” Römische Kastelle, Mainz am Rhein, p.62, fig.27.

Kolendo, J. 1969. “Dea Placida à Novae et le culte d’Hécate la bonne Déesse.” Archeologia (Warszawa) 20, 77-84.

Kolendo,

J. 1977. “Le recrutement des legions au temps et la creation de la

legio I Italica.” Akten des XI. Internationalen Limeskongresses.

Budapest, 399-408.

Milcheva, A. 1991. “Zum Problem der Datierung

der frühesten Perioden des Militärlagers Novae.” in Roman Frontier

Studies 1989. Proceedings of the XVth International Congress of Roman

Frontier Studies. University of Exeter Press, 271-276.

Milcheva, A. and E. Gencheva. 1991. “Scamnum tribunorum du camp militaire Novae.” Archaeologia (Sofia) 2, 24-35.

Milcheva,

A., and E. Gencheva. 1996. “Die Architektur des römischen Militärlagers

und der frühbyzantinischen Stadt Novae (Erkundungen 1980-1994).” in

Roman Limes on the Middle and Lower Danube. Cahiers des Portes de Fer,

Monographies 2, Belgrade, 187-193.

Mrozewicz, L. 1981. “Municipium Novae -problem lokalizacji.” - in Novae-Sektor Zahodni 1976-1978, Poznan, 197-200, p. 226.

Mrozewicz,

L. 1981. “Stellung Novae in der Organisationsstruktur der römischen

Provinz Moesia Inferior (I-III Jh.).” Eos 79, 1, S. 121

Mrozewicz,

L. 1984. “Ze studión nad role “Canabae” w procesie urbanizowania

terenów pogranicza Rénsko-Dunajskiego w okresie Wczesnego Cesarstwa.”

Balcanica Posnaniensia (Poznan) 3, 285-297.

Naydenova, V. 1988.

“Le Mithraeum recemment decouvert à Novae (Mésie inféreure).” Akten des

XIII Internationalen Kongresses für klasische Archäelogie. Berlin,

607-608.

Oldenstein-Pferdehirt, B. 1984. “Die Geschichte der Legio VIII Augusta.” JRGZ 31, 397-433.

Parnicki-Pudelko, S. 1981. “Canabae Novae: problem lokalizacji.” in Novae - Sektor Zachodni 1976-1978. Poznan.

Parnicki-Pudelko, S. et al. 1986 (1987). “Novae - Sektor Zachodni, 1984.” Archeologia (Warszawa), 131-147.

Parnicki-Pudelko, S. 1990. Novae - Sektor Zachodni. The Fortifications in the Western Sektor of Novae. Poznan.

Poulter,

A. 1994. “Novae in the 4th Century AD: City or Fortress? A Problem with

a British perspective.” in Limes. Studi di storia 5. Bologna, 139-148.

Press,

L. 1986. “Valetudinarium at Novae.” in Studien zu den Militärgrenzen

Roms III. Vorträge des 13. Internationalen Limeskongresses, Aalen,

1983. Stuttgart, 529-535.

Press, L. 1987. “The Valetudinarium at

Novae after Four Seasons of Archaeological Excavations.” in

Ratiariensia, Vol. 3-4. Convegno internazionale sul Limes danubiano,

Vidin, 1985. Bologna, 177-184.

Press, L. 1988. “Valetudinarium at Novae and other Roman Danubian Hospitals.” Archeologia (Warszawa) 39, 69-89.

Press,

L., and T. Sarnowski. 1990. “Novae. Römische Legionslager und

frühbyzantinische Stadt an der unteren Donau.” Antike Welt, Mainz, 4,

225-243.

Prostko-Prostynski, J. 1997. “Theodoric the Great in

Novae: some remarks on the chronology of events.” in Biernacki (ed.),

op. cit. 21-30.

Sarnowski, T. 1983. “La forteresse de la légion I Italica à Novae et le limes de sud-est de la Dacie.” Eos 71, 265-276.

Sarnowski, T. 1985. “Die Legio I Italica und der untere Donauabschnitt der Notitia Dignitatum.” Germania 63, No.1, 107-127.

Sarnowski,

T. 1985. “Bronzefunde aus dem Stabsgebäude in Novae und

Altemetaldeports in den römischen Kastellen und Legionslagern.”

Germania 63, No.2.

Sarnowski, T. 1986. “En merge de la

discussion sur l’origine du nom de la ville de Novae en Mésie

inférieure.” Klio 68, No.1, 92-101.

Sarnowski, T. 1987. “Zur

Truppengeschichte der Dakerkriege Traians. Die Bonner legio I Minervia

und das Legionslager Novae.” Germania 65, No.1, 107-121.

Sarnowski, T. 1988. “Wojsko rzymskoe w Mezji Dolney I na pólnocnym wybrzezu morza czarnego.” Novaensia, Warszawa, 3.

Sarnowski, T. 1988. “Römisches Heer im norden des Schwarzen Meeres.” Archeologia (Warszawa) 38.

Sarnowski,

T. 1990. “Novae Italicae im l.Jh.n.Chr.” Travaux du Centre

d’archéologie méditerranéenne de l’Academie polonaise des sciences,

t.30. Etudes et travaux, No.15, Warszawa, 349-355.

Sarnowski, T.

1990. “Die Anfänge der spätrömischen Militärorganisation des unteren

Donaulimes.” in Akten des 14. Internationalen Limeskogresses 1986 in

Carnuntum, Teil 1 und 2. Wien, 855-861.

Sarnowski,

T. 1991. “The Headquarters Building of the Legionary Fortress at Novae

(Lower Moesia).” Roman Frontier Studies 1989. Proceedings of the XVth

International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies. University of Exeter

Press, 303-307.

Sarnowski, T. 1992. “Das Fahnenheiligtum der

Legionslagers Novae.” in Studia Aegaea et Balcanica in honorem Prof. L.

Press. Warszawa, 221-232.

Sarnowski, T. 1989. “Niedermösien

während der Dakerkriege Domitians und Trajans.” Bemerkungen zu K.

Strobel, Die Donaukriege Domitians, Bonn, 1989. Eos 80, 154-155.

Sarnowski, T. 1995. “Another Legionary Groma Gate Hall? The Case of Novae in Lower Moesia.” in Biernacki (ed.) op. cit. 37-40.

Sarnowski,

T. 1996. “Die römische Anlegestelle von Novae in Moesia Inferior.”

Roman Limes on the Middle and the Lower Danube. Cahiers de Portes de

Fer, Monographies 2. Belgrade, 195-200.

Sarnowski, T. 1997.

“Legionsziegel an militärieschen und zivilen Bauplätzen der

Prinzipatszeit in Niedermoesien.” in Roman Frontier Studies,1995.

Proceedings of the XVIth International Congress of Roman Frontier

Studies, Kerkrade. Oxbow Monograph 91, Oxford, 497-500.

Sarnowski, T. 1998. “Novae. Western Sektor 1995-1997.” Archeologia (Warszawa) 49.

Sarnowski,

T. 1999. “Die Principia von Novae im späten 4. und frühen 5 Jh.” in Der

Limes an der unteren Donau von Diokletian bis Heraklios. Sofia, 56-63.

Sarnowski,

T., and J. Trynkowski. 1986. “Legio I Italica - Liburna - Danuvius.” in

Studien zu den Militärgrenzen Roms III. Vorträge des 13.

Internationalen Limeskongresses, Aalen, 1983, Stuttgartr, 536-541.

Sarnowski,

T., and P. Dyczek. 1990. “Novae in 1987 - West Sektor. Results of the

Polish Archaeologocal Expedition.” Klio, Berlin, 72, 1, 173-178.

Sarnowski,

T., and P. Dyczek. 1991. “Novae in 1989 - West Sektor. Results of the

Polish Archaeological Expedition.” Klio, Berlin, 73, 2, 489-494.

Schreiner,

P. 1986. “Städte und Wegenetz in Moesien, Dakien ind Thrakien nach dem

Zeugnis des Theophylaktos Simokates.” in Spätantike und

frühbyzantinische Kultur Bulgariens zwischen Orient und Okzident. Wien,

25-29.

Scorpan, C. 1980. Limes Scythiae. BAR, International Series 88. Oxford.

Speidel, M. 1987. “Spätrömische Legionskohorten in Novae.” Germania 65, 240-242.

Strobel,

K. 1984. “Untersuchungen zu den Dakerkriegen Trajans. Studien zur

Geschichte des mittleren und unteren Donauraumes in der Hohen

Kaiserzeit”. Antiquitas, Reihe 1, Band 33. Bonn.

Strobel, K.

1988. “Anmerkungen zur Truppengeschichte des Donauraumes in der hohen

Kaiserzeit, I: Die neuen Zigelstempel der Legio I Minervia aus dem

Lager der Legio I Italica in Novae in Moesia Inferior.” Klio 70, No.2,

501-511.

Strobel. K. 1989. Die Donaukriege Domitians. Antiquitas, Reihe 1, Band 38. Bonn.

Zahariade, M. 1988. Moesia Secunda, Scythia si Notitia Dignitatum. Bucuresti. 607-608.

This article appears on pp.35-42 in Vol.2, No.3 of Athena

Review.

.

|

|