|

by Rumen Ivanov . Durostorum

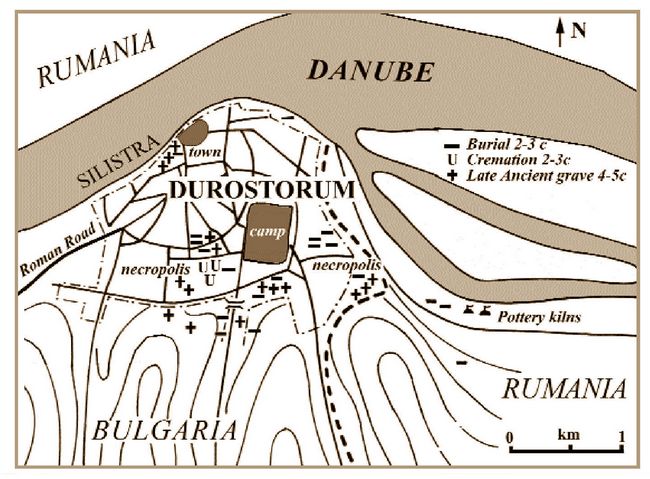

lies at the modern town of Silistra, in the northeastern tip of

Bulgaria (figs.2,3). The eastern outskirts of Silistra lie on the

Danube river, forming the border between Bulgaria and Romania. Here the

Danube forms an elbow and flows northeast toward the Black Sea.

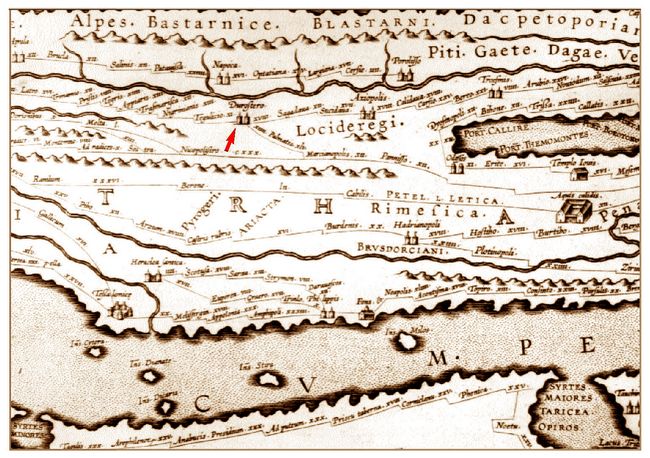

Underlying the modern settlement is Roman Durostorum, called Durostero on the Peutinger Table (fig.1), and later called

Drastar during the Middle Ages. In addition to its function as an

important Roman military center, Durostorum was also a significant

river harbor, road junction, and customs station in the province of

Lower Moesia. During the period of late antiquity, Durostorum lay

within the province Moesia Secunda, created by Diocletian betw een AD

286 and 293. een AD

286 and 293. Fig 1: A section of the Peutinger Table. Durostorum (arrow) is shown as “Durostero” (photo: R. Ivanov).

Early site history:

Durostorum and its surrounding areas were inhabited by Getic tribes,

Getae being a collective name used by ancient writers to designate

northern Thracian tribes in the northeast Balkan Peninsula, on both

sides of the lower Danube. Until now, there have been no systematic

archaeological investigations of the Thracian settlement underlying

Roman Durostorum. Its presence is indicated by occasional finds around

Silistra (fig.2), dating to the 1st millennium BC. These are kept now in the

town’s Museum of Archaeology and in private collections from Bulgaria

and Romania. Recovered articles include a bronze fibula from the 9th

century BC; a gray-black Thracian ceramic cup typical of the Early Iron

Age; a metal candlestick from the Late Iron Age, a hoard of

t hirteen

4th century drachmae minted in Histria on the western Black Sea coast;

three amphorae from the first half of the 4th century BC imported from

Heraclea Pontica; a gold earring; and a 3rd century BC gold pin

decorated with small pearls placed in gold sockets. hirteen

4th century drachmae minted in Histria on the western Black Sea coast;

three amphorae from the first half of the 4th century BC imported from

Heraclea Pontica; a gold earring; and a 3rd century BC gold pin

decorated with small pearls placed in gold sockets. Fig.2: Durostorum at the site of modern Silistra. Details of 2nd-5th c AD necropoli are in key (after P. Donevski 1990).

The

Roman era: During the reigns of Claudius (AD 41-54) and Nero (AD

54-68), the eastern border of the Roman province of Moesia (founded in

AD 12) extended to the mouth of the river Iatrus (the modern Yantra).

However, the Empire’s military control stretched along the Danube

beyond the provincial border. Durostorum was one of several important

river points already in Roman possession at that time.

The

first Roman military garrison at Durostorum was most probably composed

of an auxiliary unit. The systematic construction of the military road

along the right (southern) Danube bank had already begun to move

downstream from Singidunum (Belgrade) by Tiberius’ reign (AD 14-37).

The road section from the mouth of the Iatrus river to the Danube delta

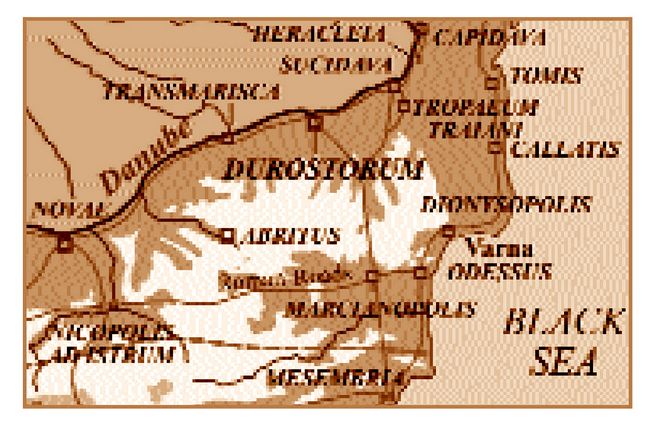

was finished under the Flavian emperors (AD 69-96). A side road

branched off at Durostorum and led to Marcianopolis and further

towards the south (fig.3). After the Dacian Wars of emperor Trajan in

AD 101-102 and 105-106, Durostorum was garrisoned by the legio XI

Claudia. Detachments of that legion are epigraphically recorded in

Montana in AD 136, as well as in the northern zone of the Black Sea. branched off at Durostorum and led to Marcianopolis and further

towards the south (fig.3). After the Dacian Wars of emperor Trajan in

AD 101-102 and 105-106, Durostorum was garrisoned by the legio XI

Claudia. Detachments of that legion are epigraphically recorded in

Montana in AD 136, as well as in the northern zone of the Black Sea. Fig.3: Map of Northeast Bulgaria, showing Roman sites. Durostorum

and its vicinity were strongly affected by an invasion of the Costoboci

in AD 170. The area was again hit hard by barbarian incursions during

the reign of Gordian III (AD 238-244), when the lower Danubian

provinces were several times overrun by Carps, Goths and Sarmatae. One

somber inscription from Durostorum dating to AD 238 tells of a person

who had to be ransomed from the barbarians. Reflecting insecurities of

the times, small hoards of coins, ending with the period of Gordian

III, were found even in the territory of the legionary camp.

The

great Gothic invasion of AD 250-251 brought about new troubles for

Durostorum. After the Roman army was overwhelmed in AD 251 at the

battle of Abritus (pp.49-54), in which the emperor Trajan Decius

perished, the victorious Goths ravaged adjacent regions of Lower Moesia

and retreated north of the Danube, crossing the river somewhere in the

section called Sexaginta Prista (modern Rousse).

A

fragmentary building inscription from Durostorum, dated to AD 272-273,

confirms the occurrence of a Carpic raid into Lower Moesia during the

reign of Aurelian (AD 270-275). The text tells of the victorious

campaigns of Aurelian against Zenobia, queen of Palmyra and the Carps.

“[quot] imperator Aurelianus vicit [reginam Ze]nobiam inviso[sque tyrannos et Carpos inter... Ca]rsium et Sucid[avam delevit.]”

It

also explicitly states that the Carps were defeated in a battle in the

frontier zone east of Durostorum, between Carsium and Sucidava. Many

Lower Moesian officials of high status are epigraphically documented in

Durostorum. One of these officers was Domitius Antigonu s, governor of

Lower Moesia in AD 235-236. The inscription reads: s, governor of

Lower Moesia in AD 235-236. The inscription reads:

“Divinib[us]

Romae aeternae, Ge[ni]o provinciae Moes(iae) Inf(erioris) Dom(itius)

Antigonus, v(ir) c(larissimus), leg(atus) Aug(usti) pr(o) pr(aetore)

cum Pompeia Apa, c(larissima) f(emina), coniuge et Domitiis Antigon(us)

et Ant(igonus).”

This

invocation to Roma aeterna and the provincial Genius of Lower Moesia

was made by the whole family - the governor himself, his wife Pompeia

Apa, and both sons. Fig.4: Marble head of a man from Durostorum, beginning of the 3rd century AD (photo: S. Roussev; Silistra Historical Museum, archives).

A

dedication to Jupiter has been recovered from the third quarter of the

3rd century AD set up for the health and well-being of Aurelius Dizzo,

another notable man whose name suggests Thracian origin:

“I(ovi)

O(ptimo) M(aximo) Sacrum. Aur(elius) Dizzo, v(ir) p(erfectissimus),

praes(es) prov(inciae), pro salute sua, suorumque omnium v(otum)

l(ibens) p(osuit).” Jupiter,

Juno, and other Roman deities are honored in a similar, nearly

contemporary monument from the late 3rd century, set up for the

well-being of Silvius Silvanus:

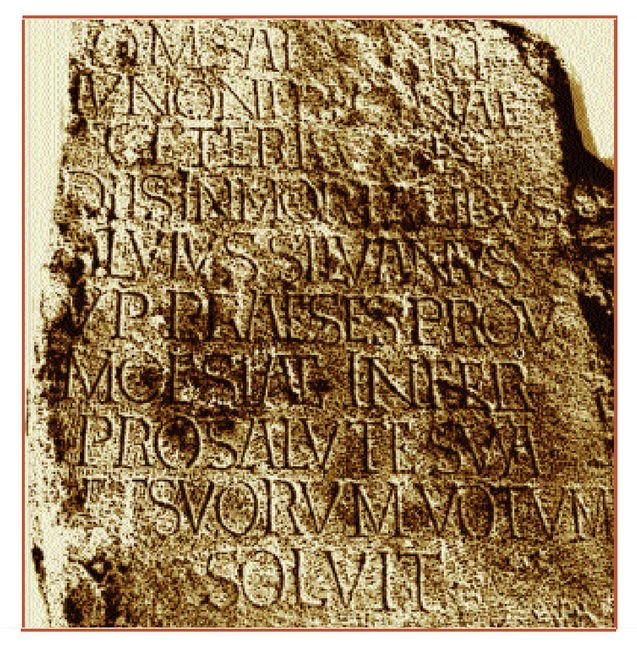

"I(ovi)

O(ptimo) M(aximo) Sal[uta]ri, Iunoni Reginae ceterisque Diis

inmortalibus [S]ilvius Silvanus, v(ir) p(erfectissimus), praeses

prov(inciae), pro salute sua et suorum votum solvit.” (fig.5).

Fig.5: Dedicatory inscription of Silvius Silvanus (P.Donevski 1976).

As

in each important military center, individuals from all parts of the

Empire could be encountered in Durostorum. Finds of inscriptions,

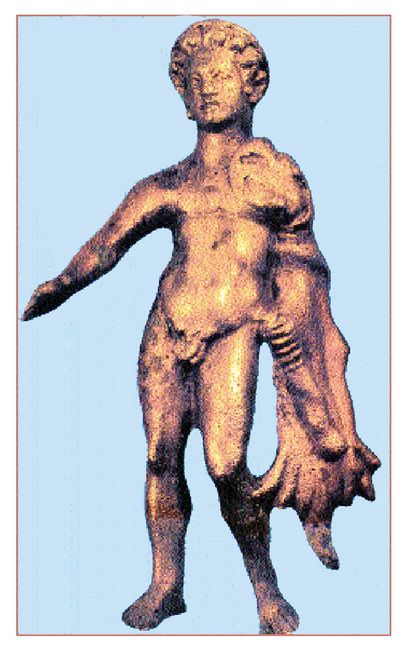

votive tablets and other sculptured monuments dating from the 2nd and

3rd centuries AD show worship in a number of religious cults including

those to the deities Jupiter, Juno, Hercules (fig.6), Mithras, and

Dolichenus. The high popularity of the Thracian Horseman deity points

to a considerable indigenous population in Durostorum. Saturn was also

esteemed, and special feasts in his honor (Saturnalia) were organized

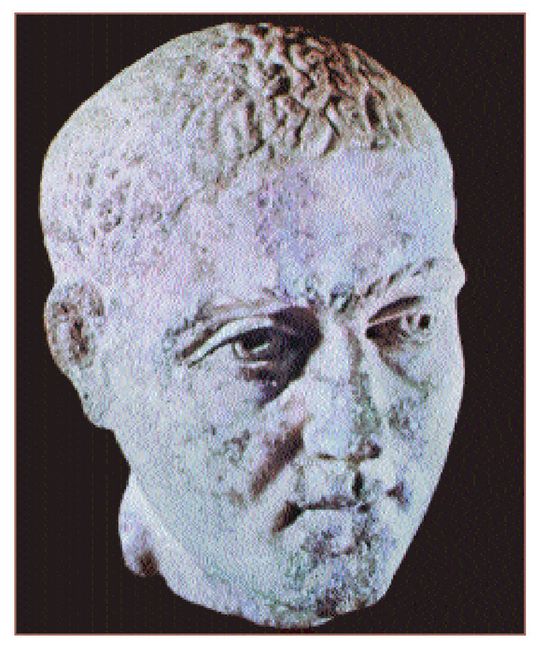

yearly. Among a several examples of Roman portrait sculpture known

from Durostorum is a life-size marble head of a man dating from the 3rd

century AD (fig.4). As

in each important military center, individuals from all parts of the

Empire could be encountered in Durostorum. Finds of inscriptions,

votive tablets and other sculptured monuments dating from the 2nd and

3rd centuries AD show worship in a number of religious cults including

those to the deities Jupiter, Juno, Hercules (fig.6), Mithras, and

Dolichenus. The high popularity of the Thracian Horseman deity points

to a considerable indigenous population in Durostorum. Saturn was also

esteemed, and special feasts in his honor (Saturnalia) were organized

yearly. Among a several examples of Roman portrait sculpture known

from Durostorum is a life-size marble head of a man dating from the 3rd

century AD (fig.4).

Fig.6: Bronze statuette of Hercules from the early 3rd century AD (Silistra Historical Museum, archives).

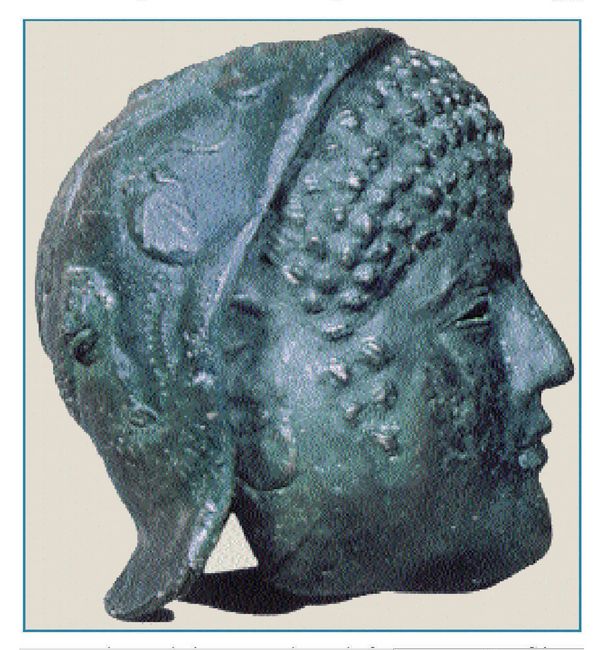

A

bronze Roman parade mask (fig.7) and a standard soldier's helmet were

both found within the town limits of Silistra (now at the Museum of

Archaeology). Another striking example of a cavalry parade helmet

(fig.8) was added to the museum in 1984. Unfortunately missing is the

front mask of this piece, which was also used in athletic competitions.

Its surface is richly decorated with representations of Sol Invictus,

Athena and another deity (perhaps Mars). Discovered on a bank of the

Danube near the ancient settlement named Tegulicium (west of

Durostorum), the helmet is dated to the 2nd or 3rd quarter of the 3rd

century. Fig.7: A bronze legionary parade mask from Durostorum (Silistra Historical Museum, archives).

Durostorum

was twice visited by the emperor Diocletian (AD 284-305) during his

inspection of the lower Danube frontier or limes on October 21-22, AD

294 and once again on June 8, 303. The emperor Valens (364-378) also

stayed in Durostorum for a significant amount of time during the First

Gothic War of 366-369. The Visigoths, granted the status of Roman

foederates in AD 376, settled in Thrace, then crossed the Danube under

pressure from the Huns, and entered the Empire in great numbers near

Durostorum (one of the catalysts for the eventual collapse of the

Empire in the early 5th century AD).

Fig.8: A 3rd c. AD bronze cavalry helmet from Tegulicium (photo: G. Atanasov; Silistra Historical Museum, archives). The

city is also the birthplace of the famous late Roman military commander

Flavius Aetius, who is perhaps best known for defeating Attila the Hun.

According to Gothic historian Jordanes, Aetius “descended from the

people of the extremely brave Moesians” (Getica, 176). Aetius commanded

the united forces of the Roman Empire and its Frankish, Burgundian,and

Visigothic allies against the Huns who, led by Attila, invaded the

Empire in the middle of the 5th century. The decisive battle took place

in July of AD 451 at the Catalaunian Fields in northern France, ending

with the utter defeat of Attila. However, the glory and increasing

prestige of Aetius frightened emperor Valentinian III (AD 424-455), and

he ordered the general’s murder on September 21, AD 454.

Durostorum

was an important center of early Christianity, which had spread

considerably by the latter part of the 3rd century. In the 4th century

the bishopric of Durostorum was held for many years by Auxentius, a

disciple of the Gothic bishop Ulfila. The latter, who translated the

Bible into the Gothic language, was the leader of the so called Gothi

minores. These Arrian Christians in AD 348 were granted permission to

settle in the Roman Empire in the region of Nicopolis ad Istrum, near

the modern village of Nikyup in the Veliko Tarnovo district (fig.3).

The famous Christian martyr Dasius was born in Durostorum, where his

relics were kept until the late 6th century when they were transported

to Ancona in Italy, where they are still preserved in the cathedral of

St. Cyriacus.

Barbarian

foederates of different ethnicity were included among the population of

Durostorum in late antiquity. Also present from the 4th century onward

were Goths, and, in the 6th century, Slavs. The city was repeatedly

attacked and plundered by Avars and Slavs in the end of the 6th through

the 7th centuries AD. Immediately after the establishment of the

Bulgarian Kingdom on the Lower Danube in AD 681, Durostorum (renamed

Drastar) became one of its most important strategic strongholds.

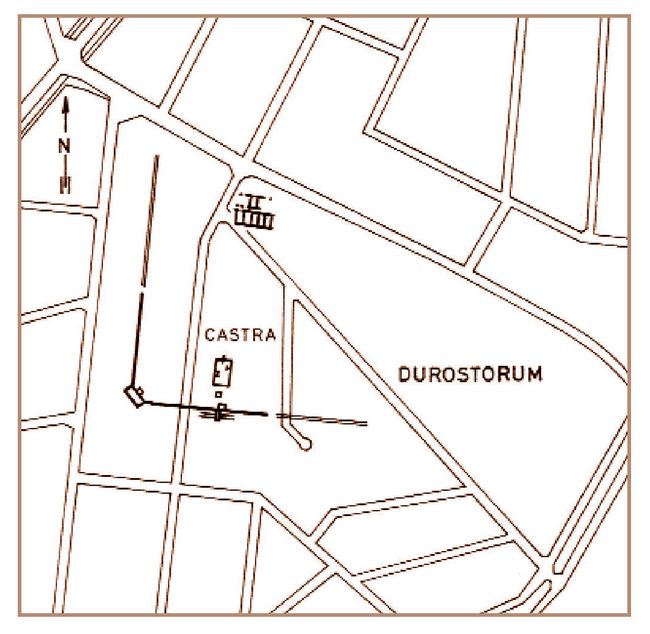

Archaeology

of the legionary camp: The remains of Roman Durostorum lay just beneath

the central portion of modern-day Silistra, mak ing it especially

difficult to carry out archaeological excavations at the site.

Investigations led by P. Donevski from 1972 to 1981 succeeded in

locating and partially revealing the layout of the ancient legionary

camp, or castra (figs.2,9). Situated 1 km south of the Danube bank with

fortified areas amounting to 17.3 ha, the camp had a rectangular plan

with rounded corners, and measured roughly 480 m (N-S) by 360 m (E-W). ing it especially

difficult to carry out archaeological excavations at the site.

Investigations led by P. Donevski from 1972 to 1981 succeeded in

locating and partially revealing the layout of the ancient legionary

camp, or castra (figs.2,9). Situated 1 km south of the Danube bank with

fortified areas amounting to 17.3 ha, the camp had a rectangular plan

with rounded corners, and measured roughly 480 m (N-S) by 360 m (E-W).

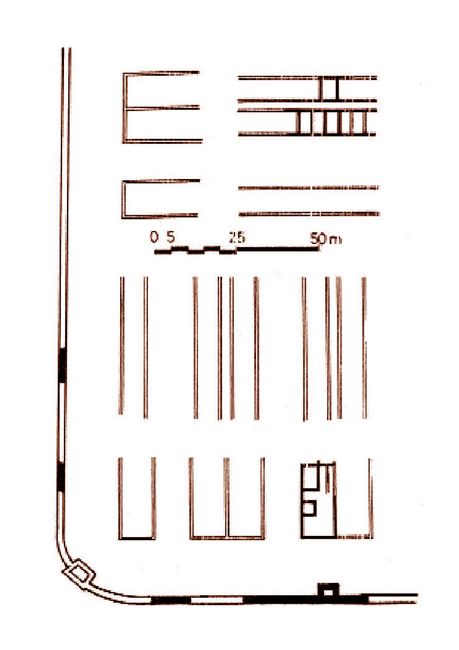

Fig.9: Durostorum’s military camp or castra set amid the street plan of modern Silistrum (after P. Donevski 1995).

While

relatively little information is available on the earliest building

phase, the fortification system has been studied in several areas.

Initially the wall was about 1.50 m thick and was reinforced with inner

rectangular towers. One such tower measuring 6.4 by 3.4 m has been

excavated on the southern precinct wall, west of the supposed main

gate, or porta decumana. Its foundations are entirely built in opus

caementicium (masonry work), while the superstructure, with only two to

three surviving rows, is faced with small stone blocks on both sides

(opus vittatum).

Other

defensive works in the camp’s perimeter include the tower in the

southwest corner, also excavated. Situated 69 m west of the southern

precinct tower just mentioned, it is trapezoidal in plan (9.4 by 7.95

m).While generally dated to the first half of the 2nd century AD, some

of these defenses may actually originate from the time of Trajan who,

in AD 106, transformed Durostorum into a legionary base and stationed

the legio XI Claudia there after the end of the Second Dacian War. Fig.10: Southwest corner of the legionary camp, with barracks at north (after P. Donevski 1995).

Among

the few buildings excavated within the camp is a structure 17 m north

of the southern wall, of which 260 m2 have been uncovered. It consists

of two rows of rooms placed on either side of a central corridor. Only

one chamber (4.45 by 3.95 m) in the western part of the building has

been entirely preserved. The structure is thought to have been a

centurion’s dwelling. Presuming that his centuria lay nearby,

archaeologists have found remains of two barracks 150 m north of the

southern precinct wall (fig.10). Both have an east-west orientation and

measure 8.5 m wide. The barracks consist of many rooms of similar size,

measuring 3.8 by 4.4 m, only six of which have been entirely excavated.

The

legionary camp at Durostorum was reconstructed in the late 3rd century

during the reign of either Aurelian or Diocletian. A new type of mortar

was used for this building project - pink in color, containing a

mixture of small tile and brick pieces. The thickness of the precinct

wall was increased to 2.6 m and a large new tower appeared at the

south-west corner. The latter tower of rectangular plan projected

slightly outwards and measures 21.7 by 12.8 m (fig.10).

The

canabae: A dedication to Jupiter found in Silistra and dated to AD 145

(CIL III 7474) reads that two wealthy citizens set up a statue on

behalf of the cives Romani et consistentes in canabis Aeliis. This

inscription unequivocally proves that a canabae, or veterans’

settlement around the castra, was already established in Durostorum by

the time of Hadrian’s reign (AD 117-138). The canabae were situated

north, west, and northwest of the legionary camp, covering 60 to 75

acres (fig.2).

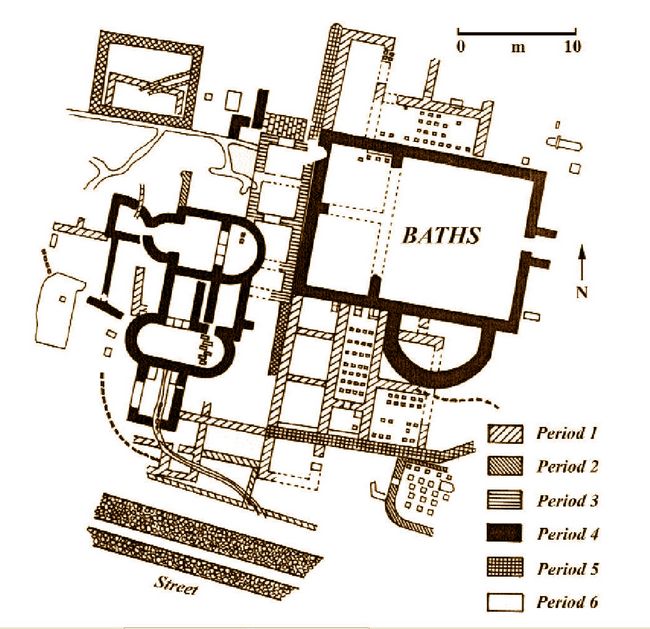

Up

to the present, several buildings hav e been partially excavated in the

territory of the canabae, one being a public bath located some 250 m

north of the camp. Built in the first half of the 2nd century, it had a

continuous plan of linked buildings facing southwest (fig.11). Bathers

were provided with three pools for warm water and one pool (piscina)

containing cold water. During the following centuries, the bath

underwent several major reconstructions, with the latest repairs dating

to the middle of the 4th century AD. e been partially excavated in the

territory of the canabae, one being a public bath located some 250 m

north of the camp. Built in the first half of the 2nd century, it had a

continuous plan of linked buildings facing southwest (fig.11). Bathers

were provided with three pools for warm water and one pool (piscina)

containing cold water. During the following centuries, the bath

underwent several major reconstructions, with the latest repairs dating

to the middle of the 4th century AD. Fig.11:

Baths in the canabae at Durostorum, and residential buildings to the

south. Six periods of construction are indicated between the 2nd and

4th centuries AD (after P. Donevski 1990).

During

recent excavations of the baths, floor bricks stamped with the name

RVMORIDVS were found in one room. This refers to Flavius Rumoridus, who

because of his contributions to the general reconstruction and

refortification of the province in the 4th century, is thought to have

been dux provinciae Moesiae Secundae. In AD 384 he was promoted to the

rank of magister militum, and in AD 403, towards the end of his career,

he was appointed consul of Constantinople.

In

addition to the public bath, a large private building to the southwest

has been discovered dating to the mid-2nd century AD. Rooms in the

northern and southern ends of the structure were insulated for heating

by hypocaust or underground furnace with wall ducts. In the beginning

of the 3rd century a small bath composed of a row of rooms, each

supplied with a hypocaust, was built against the western wall of this

building. All structures were dismantled a century later, and on top of

the ruins newer and larger buildings were constructed with exedrae or

semicircular porticoes in the southeast ends. A sun-dial dating from

the beginning of the 3rd century was also found in situ some 120 m

north of the structures with hypocausts just described. Detailed

analyses suggest the central square of the canabae of Durostorum may

have been located at this very place.

Durostorum

as a municipium: The administrative status of Durostorum was elevated

to that of a municipium in the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD. Key

evidence for this comes from the village of Ostrov, Rumania, some 4 km

east of Silistra. Numerous significant finds at this site prove the

existence in Roman times of a large vicus, or native Thracian town. One

Latin inscription engraved on a block of stone and reused as building

material in a late antique structure had a dedication to Jupiter and

Juno for the health of the emperor Marcus Aurelius  Antoninus, and the

municipium Aurelium Durostorum. It mentions six dedicators, all members

of Durostorum’s city administration. Antoninus, and the

municipium Aurelium Durostorum. It mentions six dedicators, all members

of Durostorum’s city administration.

While

some scholars suggest that Durostorum was granted a municipal status

during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (AD 161-180), others consider the

emperor named in the text to be M. Aurelius Antoninus Caracalla (AD

211-217). Another unresolved question concerns which of the two civic

settlements in the vicinity of Durostorum, the canabae or the vicus,

was elevated in rank to municipium, or self-governing city.

Fig.12: The excavated area on the Danube bank (after S. Angelova 1973).

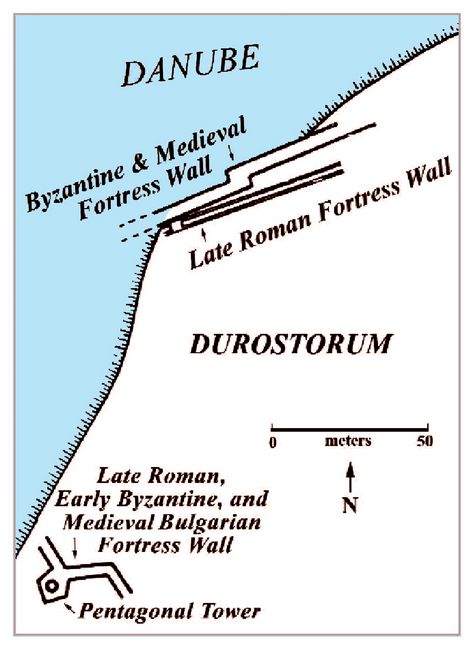

Excavations

on the Danube bank in Silistra led by S. Angelova from 1969 to 1971

resulted in the discovery of late Roman, Byzantine, and medieval

fortifications (fig.12). A 55 m section of circuit wall was unearthed,

with the equivalent of two rows’ height preserved. The late Roman wall,

2.3 to 2.6 m thick, was built of rectangular stone blocks cemented with

pink mortar on both faces. The fortification may be identified with the

newly built praesidium or headquarters building mentioned in a

legionary inscription from Silistra, dated to AD 298-299. Similar

inscriptions from the same period are also known from Sexaginta Prista

(Rousse) and Transmarisca (Tutrakan), the latter dismantled and

rebuilt during the reign of Justinian I (AD 527-565). A pentagonal

tower from this fortification has also been excavated (fig.12). By this

time, the garrison of late ancient Durostorum is thought to have been

stationed in new fortifications on the Danube bank, to the southwest of

the earlier fortress walls. Constructions

dating from the 5th to 6th centuries AD have also been discovered

within the walls of the old legionary fortress, whose territory was

probably settled by a civilian population in late antiquity.

Interestingly, written accounts by the empress Anna Comnena (AD

1083-1148) indicate two fortresses in Durostorum were still standing at

the beginning of the 11th century.

Grave

Finds from Durostorum: Several necropoli located around Roman

Durostorum include both cremation urns and extended burials (fig.2).

One necropolis is 2 km east of the central portion of Silistra, and

another, dating to late antiquity with some Christian interrments, is

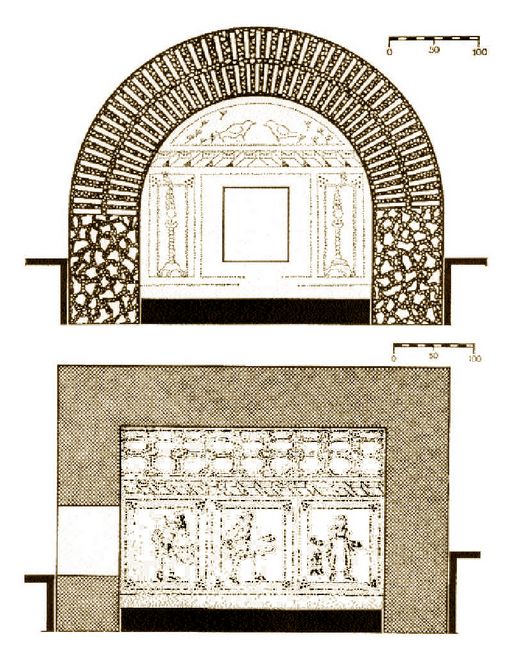

situated on the southeastern edge of the modern town. Fig.13: Cross-section of the Silistra tomb (Silistra Historical Museum, archives). The

Silistra Tomb: In 1942 a late Roman tomb containing well-preserved wall

paintings was accidentally discovered southeast of the town center in

Silistra, at a depth of only 0.7 m beneath ground level. The tomb is a

single-chambered vaulted building with a rectangular plan of 3.3 by 2.6

m, with a maximum height of 2.3 m (fig.13). The tomb’s stone walls (0.6

m thick) are joined by reddish-white mortar, while the vault, composed

of two rows of mortered brick, begins from a height of 1 m. The floor

is paved with bricks, with the entrance on the east side of the

building. In 1964 preservation efforts began on the tomb, which is

surrounded with a special protective coat to shield it from damaging

conditions.

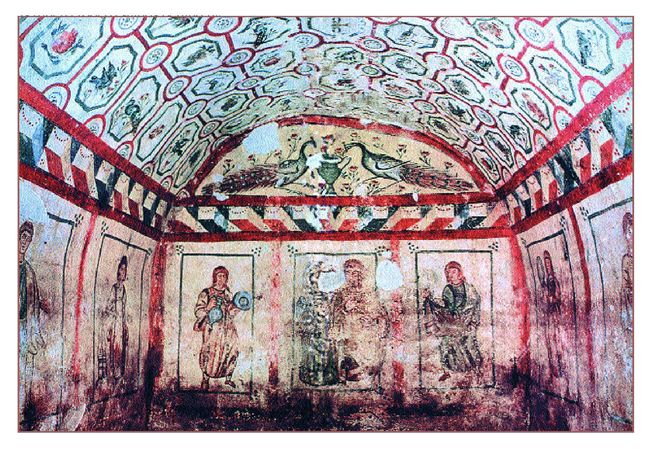

The

tomb is decorated with polychrome wall paintings divided into upper and

lower registers or pictorial zones, on the vault and on the walls

themselves (fig.14). The subject matter of these paintings is the representation

of heavenly paradise and the beauty of the next world. Juxtaposed is a

lower band of paintings illustrating mortal existence, according to a

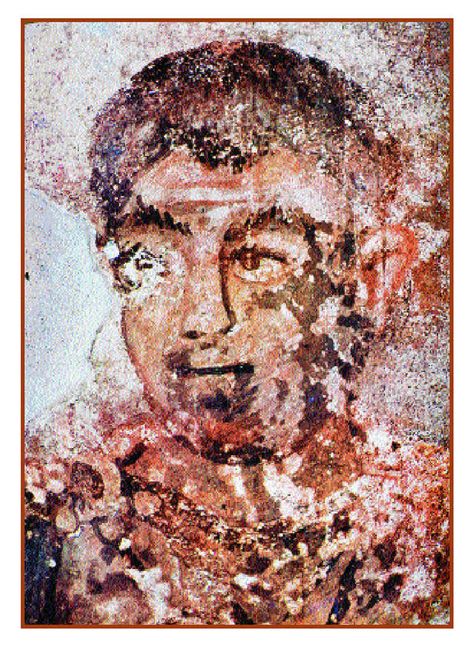

tradition established in the Hellenistic period. Fig.14: The west half of the tomb at Silistra (photo: K. Tanche v; Silistra Historical Museum, archives). v; Silistra Historical Museum, archives). Each

of the walls, with the exception of the eastern one, is divided into

three separate rectangular pictorial fields. On the west wall, a couple

is depicted on the central plane (fig.14). The man, with closely

cropped hair and a coarse face, is dressed in a tunic and mantle and

holds a scroll in his hand, possibly a marriage settlement (fig.15). Fig.15: The face of the deceased master, west wall of tomb (Silistra Historical Museum, archives).

His

wife (whose head is much eroded) stands behind him, dressed in a

long-sleeved tunic with a kerchief on her head. While her left hand

rests on her husband’s shoulde r, she holds a rose in her right hand. r, she holds a rose in her right hand. In

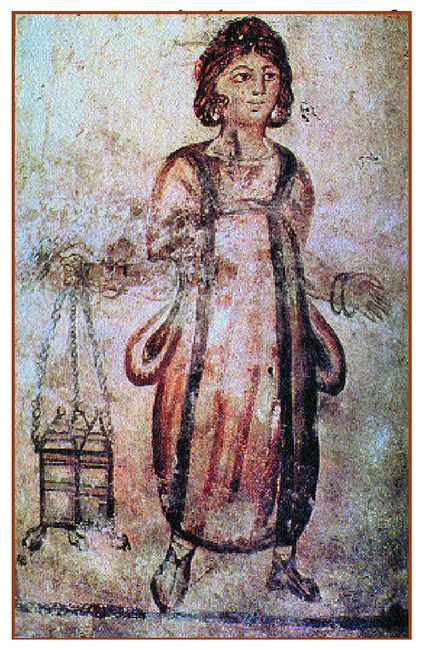

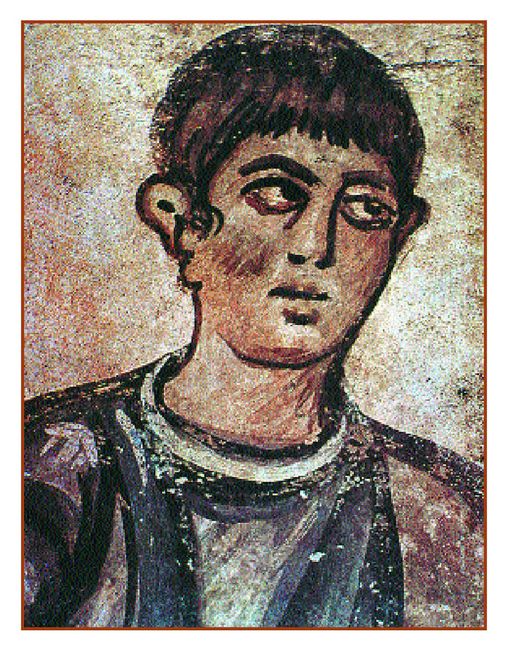

north and south panels, male and female servants approach their masters

carrying garment s and toiletries (figs.16-18). Among the men are Goths,

as well as representatives of other nations. s and toiletries (figs.16-18). Among the men are Goths,

as well as representatives of other nations.

Fig.16 (left): Female servant from south wall (Silistra Historical Museum, archives).

Fig.17 (right): Male servant, middle field on north wall (Silistra Historical Museum, archives).

The

eastern wall has two fields with funeral torches represented on either

side of the entrance. Painted bands of trim separate the lower

pictorial band from the vault. Two birds, perhaps pigeons, with ribbons

in their beaks are represented on the eastern lunette, balancing two

peacocks on the west wall on either side of a bronze vessel

(cantharos). The decoration of the vault imitates a casette, or paneled

ceiling, whose fields contain 63 smaller paintings of vegetation and

animal motifs, as well as hunting scenes.

There

are two somewhat differing views on the dating of the late antique

Silistra tomb. D. P. Dimitrov and M. Chichikova date the structure to

the last quarter of the 4th century. Based on the style of mural

painting, however, Drs. V. Popova and J. Valeva prefer an earlier date

in the fourth or fifth decade of the 4th century. Ev en

from a purely

historical point of view, the latter time period seems the more

likelyof the two. It is difficult to believe that such an elaborate example

of tomb architecture would have appeared after the disastrous Gothic

invasion of AD 376-378, an event which severely ravaged the region and

ushered in years of disorder and economic collapse. en

from a purely

historical point of view, the latter time period seems the more

likelyof the two. It is difficult to believe that such an elaborate example

of tomb architecture would have appeared after the disastrous Gothic

invasion of AD 376-378, an event which severely ravaged the region and

ushered in years of disorder and economic collapse.

Fig.18: Servant on the south wall (Silistra Historical Museum, archives).

Chariot

Burial of a High-Ranking Aristocrat: In autumn of 1968, during excavations in the southeast necropolis of Durostorum not far from the

Silistra tomb, the burial site of a high-ranking aristocrat was

accidentally discovered in Silistra (compare also the elaborate 2nd

century AD chariot burial more recently discovered at Tran, p.31.) At

Silistra, the deceased man had been buried in a wooden coffin whose

interior was lined with lead plates. Grave goods found with the

physical remains include a gold fibula (fig.21), two iron swords in

wooden sheaths (fig.22), four iron spear heads, a suite of silver belt

appliques (fig.19), a massive gold ring with a gem depicting the

goddess Fortuna (fig.20), and a coin of the emperor Probus (AD

276-282). coffin whose

interior was lined with lead plates. Grave goods found with the

physical remains include a gold fibula (fig.21), two iron swords in

wooden sheaths (fig.22), four iron spear heads, a suite of silver belt

appliques (fig.19), a massive gold ring with a gem depicting the

goddess Fortuna (fig.20), and a coin of the emperor Probus (AD

276-282). Fig.19: Openwork disk from a cross-belt, of silver, gold,and precious stones (Silistra Historical Museum).  The

fibula (fig.21) is an early version of bulb-headed types whic The

fibula (fig.21) is an early version of bulb-headed types whic h first

appeared in Moesia and Thrace soon after the middle of the 3rd century

and became very popular during the reign of Constantine the Great (AD

306-337). h first

appeared in Moesia and Thrace soon after the middle of the 3rd century

and became very popular during the reign of Constantine the Great (AD

306-337).

Fig.20 (left): Gold ring with gem and Fortuna emblem. Fig.21 (right): A gold bulb-headed fibula (Silistra Historical Museum, archives). The sheaths of both swords (fig.22)form large silver discs on their

ends, and the handle of one of the swords is made of silver and ends

with an elliptical plate studded with semi-precious stones. The sheath

of the same sword is completely encased in silver and features on its

exterior gilded plates encrusted with rubies and other precious gems.

The silver appliques are finely detailed with inlaid engraving (the

“nielle” technique popular in antiquity). The le ather belt holding

these swords has not been preserved. The identical style of decoration

of the two swords and the silver belt appliques appear to prove that

both were made to order simultaneously in one workshop. ather belt holding

these swords has not been preserved. The identical style of decoration

of the two swords and the silver belt appliques appear to prove that

both were made to order simultaneously in one workshop.

Fig.22: Swords and scabbards from chariot burial (photo:P.Franz;Silistra Historical Museum, archives)

Just

next to the coffin were found the remains of a four-wheeled chariot

buried during the funeral ceremony, together with the four horses

harnessed to it (see also p. 31). The chariot was richly decorated with

numerous bronze appliques and statuettes depicting gods, mythological

creatures, and  animals including Dionysos, satyrs, and a panther. The

harness was also decorated with gold lamellae or layers (fig.23).

Compared to the craftsmanship of the swords and belt appliques, the

decorated articles from the chariot are of an inferior quality,

characteristic of the mass production of local provincial workshops. animals including Dionysos, satyrs, and a panther. The

harness was also decorated with gold lamellae or layers (fig.23).

Compared to the craftsmanship of the swords and belt appliques, the

decorated articles from the chariot are of an inferior quality,

characteristic of the mass production of local provincial workshops. Fig.23: Gold appliques from harness (photo: P. Franz; Silistra Historical Museum, archives).

The chariot burial site most certainly dates to the end of the 3rd century

AD. Its unique nature is emphasized by the magnificent set of two

swords produced in a first-rate imperial atelier. The grave goods leave

little doubt that the deceased belonged to the local provincial

aristocracy, and was either a superior military commander or

high-ranking state official.

References: Ancient Sources on Durostorum

2nd

and 3rd centuries AD: Claudius Ptolemaeus (ca. AD 83-161), noting the

settlement Dourostoron in his work Geographia (III, 10, 5), provides

the earliest listing of the site. The Peutinger Table (fig.1) shows a

station called Durostero on the road from Singidunum (Belgrade) to the

Danube delta. Dorostoro is also in the 3rd century AD Antonine

Itinerary (223, 4), as both a road station and military base for the

legio XI Claudia. In AD 294, an edict of the emperors Diocletian and

Maximianus included in the Codex of Justinian (VIII, 41, 6) was issued

in Dorostolo, another ancient variant of the town’s name.

4th

century AD: The historian Ammianus Marcellinus mentions Dorostorum in

his work Rerum Gestarum Libri (XXVII, 4, 12) as an important city

located in Lower Moesia. Eusebius Hieronymus tells in his Chronicon

(XXXVIII, II) of the Christian martyr Aemilianus who was sentenced to

death and burnt in Durostorum during the reign of emperor Julian III

(AD 361-363). The name Dorostori is also seen in the Codex Theodosianus

(X1,11, anno 367). The Notitia Dignitatum, whose Lower Danube section

was compiled in AD 393-394, describes the composition of the local

garrison of the legio XI Claudia in the second half of the 4th century

(Or., XL, 26; 33).

5th and 6th centuries AD: The Synecdemus of

Hieroclis (636, 4) lists Durostolos as one of the seven cities of the

province of Moesia Secunda. Procopius in De Aedificiis (IV.7) reports

that emperor Justinian I repaired the walls of the fortress. Durostorum

is also mentioned in Books I and VI of The Historia of Theophylactus

Simocatta, regarding Byzantine military campaigns against Slavs and

Avars on the lower Danube during the reign of Mauricius. In the Ravenna

Cosmography (IV, 7) the anonymous author, following the 4th century

writer Libanius, describes Durostorum as one of the more important

cities in Moesia.

|