|

Rumen Ivanov Archaeological Institute and Museum, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia . Abritus

is located about 50 km south of the Danube (fig.1) in the northeastern

Bulgarian town of Razgrad, on the Hissarlik plateau (from Hisar,

Turkish for “fortified hill”). The Roman military base evolved from a castellum at its 1st century AD beginnings, to a walled fortress by the early 4th century AD. This settlement continued into the early Byzantine period. base evolved from a castellum at its 1st century AD beginnings, to a walled fortress by the early 4th century AD. This settlement continued into the early Byzantine period.

Fig.1: Map of present-day Bulgaria showing Roman provinces, major towns, and military sites (after S. Goshev and R. Ivanov).

Written Sources: Abritus is frequently

mentioned by ancient Greek, Latin, Gothic, and Byzantine authors in

reference to a sanguinary battle there between the Goths and the Romans in AD 251, where the emperor Decius was killed.

A

second group of records pertains to town administration and the

bishop’s residence at Abritus during the Late Ancient era of the

5th-6th centuries AD (see Ancient Sources in bibliography).

Archaeological discovery of Abritus:

Until systematic excavations began in 1953, it was believed the

Hissarlik held the ancient town of Dausdava (Dausdaua), mentioned by

the Alexandrian Claudius Ptolemaeus in his second century AD Geographia

(III, 10, 6). The most popular choice, meanwhile, for the location of

Abritus had been the village of Aptaat, northeast of Razgrad near the

Bulgarian-Romanian boundary. In 1942 this village was even (perhaps a

bit too optimistically) renamed Abrit.

The

excavations, however, conducted in 1953-1978 by the Archaeological

Institute and Museum of Sofia under Prof. Teofil Ivanov, together with

the Town History Museum in Razgrad, found decisive evidence that

ancient Abritus lay at the modern town of Razgrad. In 1954 a

sacrificial stone altar to Hercules was found in Hissarlik from the

time of Antoninus Pius (AD 135-161) Within the inscription was the name

of the legionary settlement (canabae) at Abritus:

[Her]culi

sacrum./[P]ro salute Antonini/ Aug(usti) Pii et Veri Caes(aris).

/Veterani et c(ives) Romani/ et consistentes/ Abrito ad ca[n(abas)]/

posueru[nt].

Other

inscriptions helping to verify the site’s location include a milestone

found 1.5 km east of the Hissarlik in 1980, dating from the reign of

Emperor Phillip the Arab and his son, the Caesar Phillip (AD 245-247):

Imp(eratori) Caes(ari)/ Mar(co) Iulio/ Philippo/ pio filici (sic). Per/terr(itorium) Abri(ti) /m(ille) p(assuum) I.

(“By the Emperor’s son Caesar Marcus Julius Phillip, one mile from the territory of Abritus.”) A gravestone dated to the 4th-5th century AD contains the words civ(itas) Abr(itus),

ie., “the town Abritus.” Also noteworthy is that, at eleven different

places along the ancient town’s fortification wall (figs.3,4,7,8,11),

stone blocks are inscribed with a big letter “A,” which is undoubtedly

an abbreviation for Abritus.

Site topography:

the fortified plateau of Hissarlik slopes down from the southeast above

the river Beli Lom, a tributary of the Roussenski Lom which flows into

the  Danube at Rousse, site of the Roman fort Sexaginta Prista. Since

ancient times, this fertile alluvial region has contained agricultural

and cattle-breeding fields and vineyards providing food for both civil

and military populations. Three burial grounds or necropoli (only

partially excavated, with results still unpublished) dating from Roman

and Early Byzantine periods have been revealed near Abritus, one to the

north of the settlement, and the other two located to the south and

southwest. Danube at Rousse, site of the Roman fort Sexaginta Prista. Since

ancient times, this fertile alluvial region has contained agricultural

and cattle-breeding fields and vineyards providing food for both civil

and military populations. Three burial grounds or necropoli (only

partially excavated, with results still unpublished) dating from Roman

and Early Byzantine periods have been revealed near Abritus, one to the

north of the settlement, and the other two located to the south and

southwest.

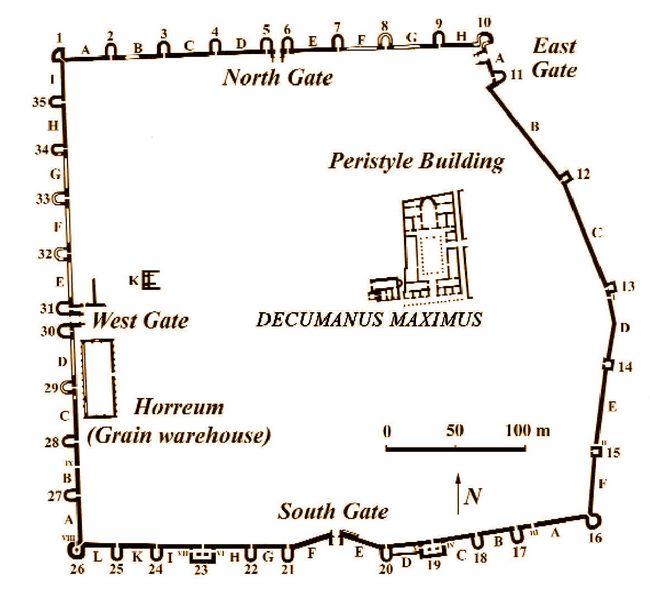

Fig.2: Layout of the castellum at Abritus, showing outer wall towers and interior structures (after T. Ivanov 1980).

The Thracian Settlement:

In 1953, during archaeological excavations at Hissarlik hill, a

previously unknown Thracian occupation was discovered. Dating from the

4th century BC, these finds show the existence of a local settlement

long before the Romans conquered this region and, during the reign of

Claudius in AD 45, founded the province of Thracia.

Shedding

new light on the Thracian dynasty and its relation to the Roman empire

was an inscription found late in 1953 by T. Ivanov, while excavating a

Christian basilica. Here a white marble tablet reused as building

material had a Greek inscription mentioning the Thracian ruler

Rhoemetalces II (fig.3)

“During the reign of Rhoemetalces over the Thracians, the grandson of

Cotys, basileus and grandson, on his mother’s side of Rhoemetalces,

basileus, son of Reskouporis, dynast of the Thracians, Apollonios... strategos of A nchialos, Selletika and Rhysika had this altar erected.” nchialos, Selletika and Rhysika had this altar erected.”

When first carved, his name went with the

title “a dynast of the Thracians.” After services rendered for Tiberius

in AD 26, however, the inscription was altered to the higher title of

king (Basileus). Within a period of only 13 years this dynasty underwent radical changes in Imperial favor.

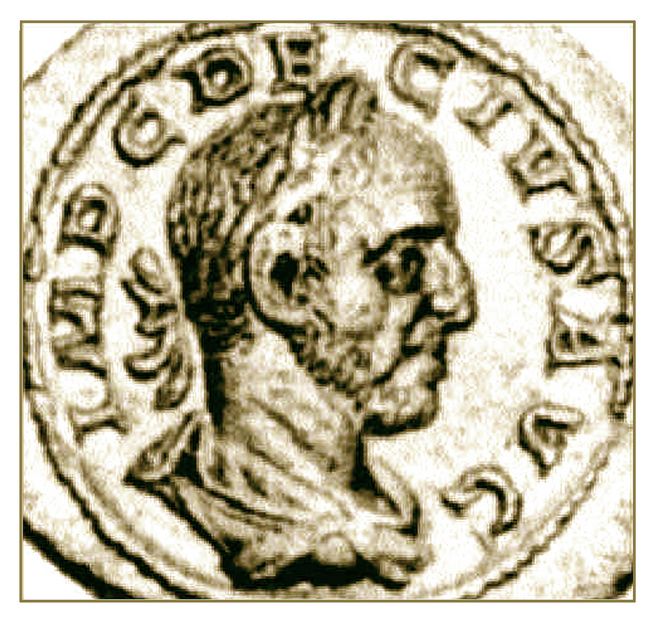

Fig.3: Coin of Thracian king Rhoemetalces II, from period of Tiberius (Athena Review). Unable

to abide this humiliation, in AD 19 Reskouporis invited his nephew and

rival Kotys III to be his guest, and then treacherously killed him.

Reskouporis was captured by the order of Tiberius (fig.4) and exiled to

Alexandria, where, the same year, he was killed in “an attempt to

escape.” Rhoemetalces II, son of Reskouporis, succeeded to his father’s title of dynast. In AD 26, new rebellions burst out and Rhoemetalces II helped the Romans with his army. For this he was given the title basileus, “King of the Thracians,” thus recovering the status enjoyed by his grandfather. II, son of Reskouporis, succeeded to his father’s title of dynast. In AD 26, new rebellions burst out and Rhoemetalces II helped the Romans with his army. For this he was given the title basileus, “King of the Thracians,” thus recovering the status enjoyed by his grandfather.

Fig.4: The Roman Emperor Tiberius (AD 14-37) on the obverse of the coin in fig.5 (SGI-5404; Athena Review).

Roman legions in Abritus:

At the end of the 1st century until AD 136, the legionary unit cohors

II Lucensium settled in Abritus. Known at the site from a gravestone

inscription, this cohort was formed in Spain. An inscription from

Montana in northwest Bulgaria shows they were in Moesia by AD 78. After

cohors II Lucensium left Abritus, it was replaced by another (still

unidentified) military unit. Unfortunately, no remains of a related

military camp have so far been discovered. Excavations in the central

and the western part of the archaeological site have been limi ted by

the presence of a modern factory. ted by

the presence of a modern factory.

Canabae and Castellum:

The makeup of the military settlement at Abritus has been much debated.

An inscription from the late 3rd century containing “Abrito ad c...”

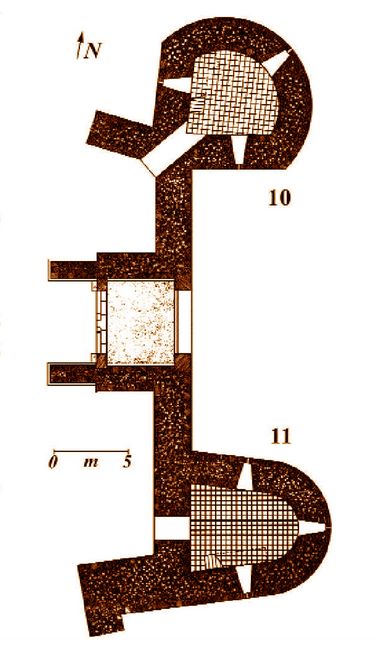

was read by Prof. T. Ivanov as ...Abrito ad c[an(abas)], referring to the canabae or town attached to the military base. An alternate reading by Prof. F. Vittinghoff, however, is ...Abrito ad c[as(tellum)], based on a parallel from CIL III 942 of ...natus in M[oe]si[a] infer(iore) castell(o) Abritan(orum), referring to the castellum. Fig.5: Plan of the East Gate (J. Furkov; in T. Ivanov and S. Stoyanov 1985).  During

this late 3rd century period in Abritus, it is known that there were

two main settlement areas, the castellani dwelling in the castle or

walled fort and the cives who lived in the civilian town. T. Ivanov’s

reading (supported by B. Gerof) is that canabae existed not only in the

more familiar structure of castra-canabae-vicus (ie., as at Novae and

Oescus), but also near a castellum, as part of a

castellum-canabae-cives formation. In another epigraphic fragment on a

monument from the late 2nd century the fixing of the boundaries of

prata publica (the public pasture) is recorded. During

this late 3rd century period in Abritus, it is known that there were

two main settlement areas, the castellani dwelling in the castle or

walled fort and the cives who lived in the civilian town. T. Ivanov’s

reading (supported by B. Gerof) is that canabae existed not only in the

more familiar structure of castra-canabae-vicus (ie., as at Novae and

Oescus), but also near a castellum, as part of a

castellum-canabae-cives formation. In another epigraphic fragment on a

monument from the late 2nd century the fixing of the boundaries of

prata publica (the public pasture) is recorded.

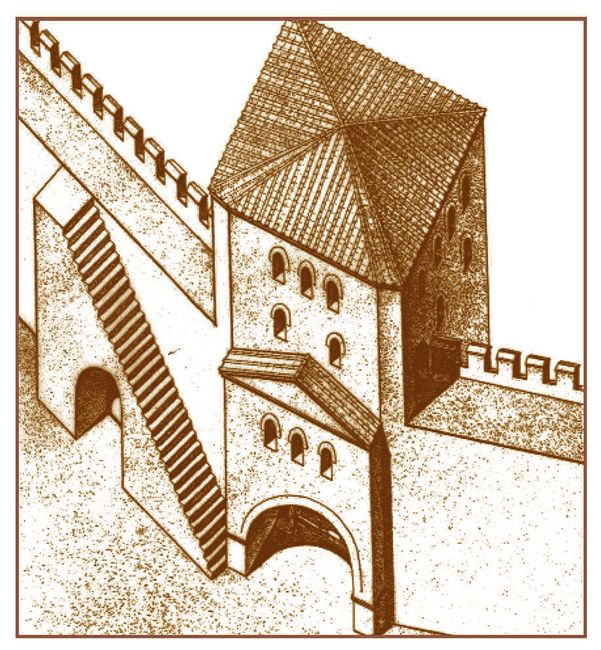

Fig.6: A reconstruction of the East Gate at Abritus (J. Furkov; in T. Ivanov and S. Stoyanov 1985). Third century Gothic invasions:

The greatest Barbarian invasion into the provinces of Lower Moesia and

Thracia during the period of the Principate was that of the Got hs in

the middle of the 3rd century. At the end of AD 248 and in early 249,

they, in conjunction with other tribes, attacked the town of

Marcianopolis (present Devnya). On the heels of this came a second big

invasion in the spring of AD 250, when the Goths crossed the Danube in

four important sections between Augustae (present village of Harlets)

and Sexaginta Prista (Rousse). The largest contingent of Goths, under

the command of their leader Kniva, besieged Novae and the castra

legionis I Italicae (pp.37-44). From there they started for the town of

Nicopolis ad Istrum. hs in

the middle of the 3rd century. At the end of AD 248 and in early 249,

they, in conjunction with other tribes, attacked the town of

Marcianopolis (present Devnya). On the heels of this came a second big

invasion in the spring of AD 250, when the Goths crossed the Danube in

four important sections between Augustae (present village of Harlets)

and Sexaginta Prista (Rousse). The largest contingent of Goths, under

the command of their leader Kniva, besieged Novae and the castra

legionis I Italicae (pp.37-44). From there they started for the town of

Nicopolis ad Istrum.

Fig.7: Reconstructed North gate, viewed from the inner side (J. Furkov; in T. Ivanov a nd S. Stoyanov 1985). nd S. Stoyanov 1985). The Roman Emperor

Trajan Decius (AD 249-251) met the Goths near the town of Augusta Traiana

(present Stara Zagora) where he was defeated. Soon after that the

Gothic forces captured Philippopolis, the largest and wealthiest town

in Thracia. The third Gothic wave came with the northward withdrawal of

the Barbarians, aimed at crossing the Danube. By this time Decius had

managed to restaff his army with new soldiers.

Fig.8: The northern fortification wall at Abritus (after T. Ivanov and S. Stoyanov 1985).  Trajan

Decius had been born in the village of Budalia, near the town of

Sirmium in present-day Serbia. The first Roman citizen from Illyricum

to became an emperor, he also had served, under the name of C. Messius

Quintus Decius Valerianus, as governor of Lower Moesia in AD 234, and

later as governor of the province of Hispania Citerior in AD 238. Decius and his wife Herennia Etruscilla are portrayed on

Roman coins (figs. 9,10). Trajan

Decius had been born in the village of Budalia, near the town of

Sirmium in present-day Serbia. The first Roman citizen from Illyricum

to became an emperor, he also had served, under the name of C. Messius

Quintus Decius Valerianus, as governor of Lower Moesia in AD 234, and

later as governor of the province of Hispania Citerior in AD 238. Decius and his wife Herennia Etruscilla are portrayed on

Roman coins (figs. 9,10).

Fig.9: Trajan Decius silver coin (Sear 2693;CNG 1997).  In AD 251

the famous battle with the Goths at Abritus brought near-catastrophic

defeat for the Romans. The Emperor Decius was fatally wounded and,

according to 4th century accounts by Eutropius and Aurelius Victor, sank on his white horse into a swamp. The next day, soldiers sought in vain for his body armor. In AD 251

the famous battle with the Goths at Abritus brought near-catastrophic

defeat for the Romans. The Emperor Decius was fatally wounded and,

according to 4th century accounts by Eutropius and Aurelius Victor, sank on his white horse into a swamp. The next day, soldiers sought in vain for his body armor.

Fig.10: Silver coin of Herennia Etruscilla, wife of Trajan Decius (Sear 2732; CNG 1997). As reported by the late Roman writer Cassiodorus in his Chronicles: the Emperor’s son Herennius also died in the battle: Decius cum filio suo in Abritto Thraciae loco a Gothis occiditur.

("The Goths killed Decius and his son in the Thracian settlement of Abritus.") Later a treaty, humiliating in its terms for

the Empire, was signed.

Abritus During the Late Empire:

After the Gothic invasions, the walls and fortications of Abritus were

significantly strengthened. Systematic archaeological excavations since

1953 have revealed the complete Late Imperial fortification system of

Abritus (fig.2). During the reign of Constantine the Great (AD

306-337), a vast fortified area or castellum of about 16 ha (40 acres)

was surrounded by walls totalling 1,400 m in length, including four

gates and thirty-five towers. The latter are primarily U-shaped,

although several are quadrangular or fan-shaped (figs.5-8,11). Fig.11: Reconstruction of the South gate at Abritus (J. Furkov; in T. Ivanov and S. Stoyanov 1985).  In

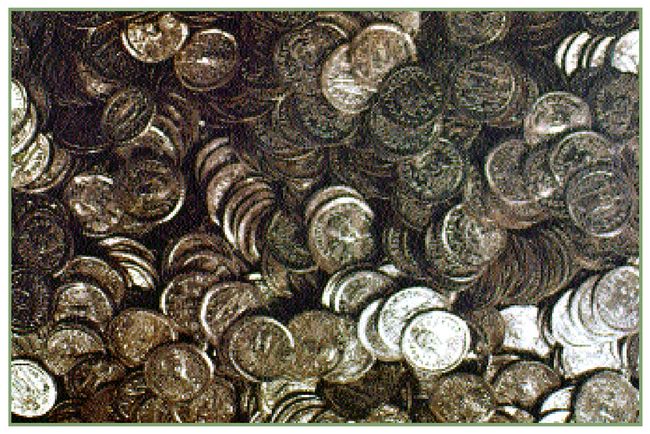

1971 a cache of 835 gold coins weighing about 4 kg was discovered along

the inner wall between towers 12 and 13. These coins (fig.12), the

largest cache found so far in the town and its environs, date from

between AD 408 and 488. They were minted in Constantinopole (Istanbul),

Thessalonika in northern Greece, and Antioch in Syria. In

1971 a cache of 835 gold coins weighing about 4 kg was discovered along

the inner wall between towers 12 and 13. These coins (fig.12), the

largest cache found so far in the town and its environs, date from

between AD 408 and 488. They were minted in Constantinopole (Istanbul),

Thessalonika in northern Greece, and Antioch in Syria.

Fig.12: A cache of 5th c. AD gold coins found by Towers 12 and 13 in Abritus (T. Ivanov and S. Stoyanov 1985).

Two early 3rd century officials at Abritus: Inscriptions from Abritus give information on two officials called beneficiarii consularis.

Their functions relate to the control of the station on the road from

Odessus through Marcianopolis and Abritus to Sexaginta Prista. Two early 3rd century officials at Abritus: Inscriptions from Abritus give information on two officials called beneficiarii consularis.

Their functions relate to the control of the station on the road from

Odessus through Marcianopolis and Abritus to Sexaginta Prista.

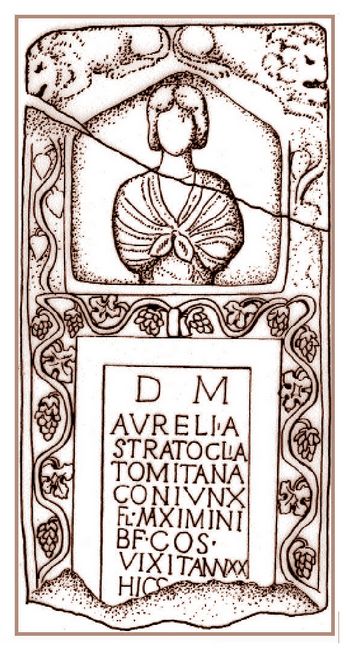

The first example (fig.13) is on the gravestone of a woman who died

around the time of Caracalla (AD 211-217).

D(is)

M(anibus) / Aurelia / Stratoclia / Tomitana / coninx / F(lavii)

M(aximi) / b(ene)f(iciarli) co(n)s(ularis), / vixit ann(is) XX / Hic

S(ita) e(st).

(“To

the underground gods Aurelia Stratoclia from Tomi (Constanca on the

Black Sea in Rumania), wife of Flavius Maximinus, beneficiarius

consularis, lived twenty years. Here is she laid.”)

Fig.13: Grave Marker of Aurelia Stratoclia from Tomi (R. Ivanov 1994).

A

second inscription, dedicated to the Celtic horse goddess Epona, dates

to the consulships of Lateus and Cerialis (AD 215):

...Eponae / Reg(inae). Pro sal(ute) D(omini) / Nostri) M(arci)

Aur(elii) Antonini [Pii] / fel(icis) Aug(usti). Val(erius) Ruf(us,

inus, inianus) / b(ene)f(iciarius) co(n)s(ularis) leg(ionis) / XI

Cl(audiae) Anto / ninianae V... / Laeto II et Ceria[le cos.]

(“To

Epona Regina. For the health of our master Marcus Aurelius Antoninus

Pius Felix Augustus. Valerius Rufus (or Rufinus, Rufinianus)

beneficiarius consularis of the 11th Claudian legion...under consuls

Laetus and Cerialis.”) Grain warehouse: Approximately

9.5 m south of the western gate was excavated a grain warehouse or

horreum with thirteen counterforts along both its east and west walls

(fig.14). The rectangular ground plan ofthe building is orientated

from north to south, with outer dimensions of 56.25 m by 20.2 m. The

warehouse was in use between the 4th and 6th centuries AD. To the n orth

of the western gate, another building has been partially uncovered. It

also has a quadrangular plan, with dimensions of 34 by 17 m. On the

shorter, southern wall was an entrance which was very near to the gate.

It is presumed that this structure was a barracks, built after the

erection of the fortification wall. orth

of the western gate, another building has been partially uncovered. It

also has a quadrangular plan, with dimensions of 34 by 17 m. On the

shorter, southern wall was an entrance which was very near to the gate.

It is presumed that this structure was a barracks, built after the

erection of the fortification wall.

Fig.14: The horreum or grain warehouse, reconstructed (J. Furkov; in T. Ivanov and S. Stoyanov 1985).

Also

discovered in Abritus were several buildings showing different stages

of construction. Excavations were carried out east of the center of the

fortified settlement, in a section which included two quarters. Four

houses were found here, each with a rectangular plan. One room in the

basal level of building no. 3 produced two coins of Emperor

Constantius (AD 337-361). Two fragments remained of a Latin inscription

built into the outer wall. This mentioned the name of Romulianus,

commander of a Dalmatian army unit [p(rae)p(ositus) equ(itum) Dalm(atarum) Beroensium commita(tensium)].  This

movable unit, whose name was unknown until recently, was stationed in

Abritus for a brief period of time. Later, on the remains of the first

two buildings was erected a third structure. This

movable unit, whose name was unknown until recently, was stationed in

Abritus for a brief period of time. Later, on the remains of the first

two buildings was erected a third structure.

Fig.15: The courtyard of the peristyle building at Abritus (T. Ivanov and S. Stoyanov 1985). All

five of the houses recently excavated (nos. I-V) had been destroyed as

a result of the Gothic invasions in AD 376-378. Here, not  more than a

few years before the end of the 4th century AD, was erected a large

building with a peristyle courtyard (figs.15,16) which revealed two

stages of construction. Initially, in a structure designated

Peristyle building VI, the southern part was built, consisting of

six shops with a central entrance in the middle and a colonnade in the

Ionic style in front of them. Later, the rest of the building was

constructed (called Peristyle building VII; fig.16). more than a

few years before the end of the 4th century AD, was erected a large

building with a peristyle courtyard (figs.15,16) which revealed two

stages of construction. Initially, in a structure designated

Peristyle building VI, the southern part was built, consisting of

six shops with a central entrance in the middle and a colonnade in the

Ionic style in front of them. Later, the rest of the building was

constructed (called Peristyle building VII; fig.16). Fig.16: A view of the peristyle building no.VII at Abritus (after T. Ivanov and S. Stoyanov 1985).

Dating

from the middle of this later phase was a rectangular yard surrounded

by a colonnade in the Roman-Ionic style, with columns 3.5 m high. Two stores or shops were situated to the east and west of the building

(fig.17). Within, nine rooms were situated on both sides of the central

rectangular hall (tablinum), a large official room entered through a

door on the southern wall containing a courtyard (fig.18). Dating

from the middle of this later phase was a rectangular yard surrounded

by a colonnade in the Roman-Ionic style, with columns 3.5 m high. Two stores or shops were situated to the east and west of the building

(fig.17). Within, nine rooms were situated on both sides of the central

rectangular hall (tablinum), a large official room entered through a

door on the southern wall containing a courtyard (fig.18).

Fig.17: Colonnade in front of the shops (after T. Ivanov and S. Stoyanov 1985). To the east

of the Peristyle building VII, along the north-south cardo, the remains

of two more quadrangular houses of the same period were discovered.

Fig.18 (right) Reconstructed courtyard at Abritus (J. Furkov; in T. Ivanov and S. Stoyanov 1985). In

1887 an early archaeologist and schoolteacher, A. Yavashov, found

remains of an old Christian basilica situated 50 m northeast of the

western gate. In 1953 T. Ivanov carried out new excavations in this

building. The basilica, dating to the middle of the 6th century AD, is

orientated east-west. Measuring 18 m in length by 13.5 m in width, it

contains three naves, a three-section narthex and a semicircular apse

before the central nave (fig.19).

Fig.19 (left): Plan of the basilica from the middle of the 6th century (after T. Ivanov and S. Stoyanov 1985) The Bulgarian Settlement: Abritus

was destroyed at the end of the 6th century by invading Avars and

Slavs. About two centuries later, in the eastern part of the Hissarlik

district, there arose a Medieval Bulgarian settlement. The new

occupants constructed simple earthen dwellings inside the larger shells

of the Roman and Late Ancient buildings. Excavations have revealed many

ovens and a number of whole and fragmented pottery vessels, as well as

metal tools dating from the Medieval period. The settlement existed

until the end of thc 10th century, but was ultimately destroyed when

large areas within present-day Bulgaria fell under the control of the

Byzantine Empire.

.

.

Bibliography:

. Ancient sources on Abritus:

On the Battle with the Goths, AD 251: The most contemporary account is

by Athenian historian P. Herennius Dexippos, who writes in his 3rd c.

AD Historical Chronicles that

the emperor and his son found their death near Abritus in the so-called

Forum Tebronii. (Decius actually died in the Forum Sempronii). The

battle is later described by 4th century historians Eutropius (AD 365)

and Aurelius Victor, and the 5th century statesman Cassiodorus (AD

487-583) in his Chronica (chap. 252). Subsequently, the 6th century Byzantine historian Jordanes, in his summary of the Goths called Getica

(103), says that “Decius was surrounded by the Goths near Abritus a

town in Moesia and perished there. This place was still called

‘Decius’s altar,’ because before the battle he offered up unusual

sacrifices” (...ad Abrito Moesiae civitatem..., qui locus hodiemque

Decii ara dicitur).

On Abritus as a town: Late ancient sources include the Synecdemus

of Hieroclis (AD 527-8), mentioning Abritus among 7 towns of the

province Moesia Secunda. Procopius of Caesarea, writing ca. AD 551 in

De aerdificiis (IV, 11) notes many towns in the Lower Danube, and

reports that the Emperor Justinian I (AD 527-565) reconstructed the

town of Abritus. chap. 252).

.

Recent sources:

Clarke, G. 1980. “Dating the Death of the Emperor Decius.” in ZPE 37, 114-116. Bonn.

Georgiev, P., G. Chobanova, I. Rahneva, and D. Dimitrov. 1991. Abritus. Razgrad.

Gerov,

B. 1961. “Zur Identität des Imperator Decius mit dem Statthalter C.

Messius Q. Valerianus.” in Band 39, 222-226. Klio, Berlin.

Gerov,

B. 1963. “Die Gotische Invasion in Mösien und Thrakien unter Decius im

Lichte der Hortfunde.” in Acta antiqua Philippopolitana, 128-146.

Serdicae.

Gerov, B. 1970. “Zum Problem dr Strategien in roemischen Thrakien.” Klio, Berlin, No.52.

Ivanov,

R. 1994. “Zwei Inschriften der beneficiarii consularis aus dem Kastell

Abritus in Moesia Inferior.” in ZPE 100, 484-486. Bonn.

Ivanov, T. 1963. “Archaeologische Forschungen in Abritus (1953-1961).” AAph, Studia archaeologica, Serdicae.

Ivanov, T. 1980. Abritus: A Roman Fort and Early Byzantine Town in Moesia Inferior. Sofia.

Ivanov, T., and S. Stoyanov. 1985. Abritus. Razgrad.

Marinova,

L., and M. Lazarov. 1962. “A New Inscription of the Strategos

Apollonios Eptaikentos.” in Bulletin dell’Institut d’Archeologie, XX,

197-203. Sofia.

Tacheva, M. 1995. “The Northern Border of the Thracia Province to the Severi.” in Thracia, Vol.11, 427-434. Serdicae (Sofia).

Velkov,

V. 1989. “Cohors II Lucensium in Moesia and Thrace.” in Acta

Archaeologica Academiae Scientarum Hungarica Vol. 41, 251, Nr. 13.

Budapest.

Velkov. V. 1991. “Inscriptions de Cabyle.” in Cabyle Vol. II, 15 (n.36). Sofia.

Vittinghoff,

F. 1968. “Die Badeutung der Legionslager für die Entstehung der

römischen Städte an der Donau und in Daiken.” Studien zur europäischen

Vor-und Frühgeschichte, 136 (n.34). Neumünster.

Vittinghoff, F.

1971. “Die rechtliche Stellung der canabae legionis und die

Herkuftsangabe castris.” Band 1, 307. Hiron, München.

This article appears in Vol.2, No.3 of Athena

Review.

.

|